Copper Comet Impactor: A NASA Success Story

More than fireworks exploded in the sky this Fourth of July. While most Americans enjoyed local parades, backyard barbecues and the company of friends, NASA was busy blasting a hole deep into a comet far out in space. The goal of the mission: To uncover valuable information about the nature and origins of Earth's solar system.

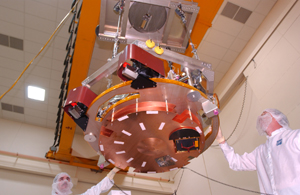

Technicians inspect copper-topped Deep Impact impactor.

Technicians inspect copper-topped Deep Impact impactor. Image Courtesy of Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp.

High-resolution version of this photo.

One of mankind's oldest metals played an integral part in this one-of-a-kind interplanetary pyrotechnics display. NASA scientists deployed a copper-topped probe called a "smart impactor" in a deliberate head-on collision with Comet Tempel 1 that occurred in the early hours of July 4.

NASA's Deep Impact mission was hailed as a dazzling success as more than 50 telescopes and 200 researchers around the world watched when the comet - traveling faster than a speeding bullet at 23,000 miles per hour - collided with the probe.

As planned, the impactor's rounded copper front-end struck the comet's nucleus on the side illuminated by the sun, causing a crater to form on the surface and dust, gas and other emissions to spew forth like a volcanic eruption. The explosion, equivalent to detonating five tons of dynamite, vaporized the impactor but did not drastically alter the trajectory of the Manhattan-sized comet.

Why Copper?

Copper, which made up half of the impactor's total mass, was selected for this mission based on several key factors, including the hardness of the metal. To make the probe even stronger, the copper was fortified with three percent beryllium.

Dr. Michael F. A'Hearn, University of Maryland astronomer, with the Deep Impact copper cratering mass.

Dr. Michael F. A'Hearn, University of Maryland astronomer, with the Deep Impact copper cratering mass. Image Courtesy of Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp.

High-resolution version of this photo.

But it was copper's molecular structure that made it ideally suited to gather data from the emissions that spewed forth from the comet after the collision. Because copper's atomic structure reacts slowly with other elements - particularly the oxygen found in cometary water - burning copper emissions did not obscure spectroscopic images taken during the crash. Other materials, such as aluminum, would have created distracting emissions and limited the effectiveness of the instrument used to monitor light reflecting from the comet.

NASA collected data from a safe distance 310 miles below the collision using the Deep Impact "flyby" spacecraft that carried the probe into space. The scientists had about 14 minutes to photograph the debris, using both optical and infrared imaging, until a blizzard of fallout from the comet blocked the spacecraft's view.

Images taken by the monitoring equipment were transmitted from the spacecraft via X-band communication. They can be viewed on NASA's Deep Impact Web site.

Comets are almost as old as Earth and our neighboring planets. Scientists believe they are made of ice, gases, rocks and dust leftover from the formation of our solar system some 4.6 billion years ago.

It will take many months before scientists have finished analyzing all the data, but they hope the debris ejected from the comet's core will lead to a better understanding of how the solar system - including our own planet - was created.

"The last 24 hours of the impactor's life should provide the most spectacular data in the history of cometary science," said Michael A'Hearn, the Deep Impact Principal Investigator. "With the information we receive after the impact, it will be a whole new ballgame. We know so little about the structure of cometary nuclei that almost every moment we expect to learn something new."

Discovered over 10,000 years ago on earth, copper is prized for its beauty, strength, durability and ability to be combined or "alloyed" with other metals to create new metals like brass and bronze. In its pure or alloyed form, copper is an indispensable material used by NASA, the U.S. military and manufacturers in various industries including: appliances, computer technology, mobile phones, wind and solar energy, plumbing tube, building construction and interior design. Cu

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Copper Comet Impactor: A NASA Success Story

- Copper Heaters Improve Fuel Tank Safety on Space Shuttle