Other Headlines

On September 7, 2004, the U.S. Patent Office granted patent number 6,786,272 to the Copper Development Association Inc. for the method it developed to permit copper and its alloys to be die cast economically. The method, familiar to readers of Update, is now used commercially to produce copper motor rotors in Europe and India (see Updates for March 10 and October 4, 2004).

Licenses to use the patented technology without fee will be issued to member companies of the CDA-led coalition that developed the new casting technique, according to Hal Stillman, director of technology for the International Copper Association, Ltd., which provided a portion of CDA's R&D funding and will oversee utilization arrangements on a global basis. "Manufacturers who did not participate in the original program and who now wish to utilize the new motor rotor technology will be charged a licensing fee," says Stillman, "and ICA will provide technological support to those companies at cost."

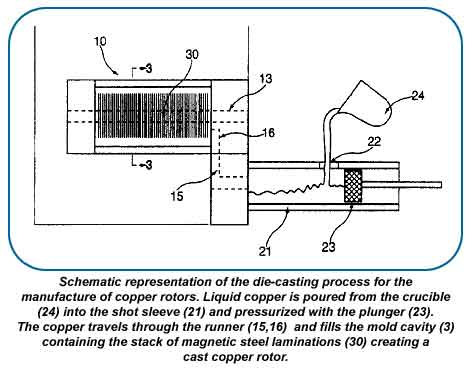

The patent discloses the essential elements of CDA's discovery, i.e., even metals with a relatively high melting point can be die cast without risking damage to the dies, if: a) the dies (or strategically placed inserts) are made from a heat-resisting superalloy and b) the temperature of the dies or inserts is maintained at a suitably elevated temperature so as to reduce the thermal stresses induced by repeated casting shots to a level that avoids cracking on the die surface - the well-known heat checking phenomenon.

The patent also makes 21 claims, the last 9 of which relate specifically to the production of motor rotors. According to Dr. John Cowie, CDA's die-cast motor rotor project manager, that's good news. But, he says, the really exciting news is to be found in the first 12 claims, which deal with the more general application of CDA's technology to the die casting of copper alloys and other materials - including aluminum and stainless steels - for the manufacture of products other than motors. Those claims open the door to an as-yet-unknown number of new applications for copper and its alloys for which the metals, for a variety of reasons, might never have been seriously considered previously.

Cowie says that's important, because pressure die casting offers a number of advantages, both technical and economic. For example, the process can yield net-shape (or near-net-shape) products with excellent surface finishes and consistent dimensional tolerances. Secondary operations, such as machining, can be reduced to a minimum and may be avoided altogether. And, because of the relatively rapid solidification rates involved, grain sizes tend to be smaller than those of sand castings, and mechanical properties are correspondingly improved. Less metal is therefore needed for equivalent load-bearing capacity.

But, just as in the case with motor rotors, pressure die casting for other castings has been limited to low-melting-point metals, such as aluminum and zinc. Copper and alloys that offered higher strength and better corrosion resistance than the light metals were excluded because no one has figured out how to make dies last long enough to justify their relatively high cost. The acceptable die life now made possible by CDA's invention means that the die-casting process could be applied to low-added-value items, such as gear blanks and mass-produced mechanical parts, hardware and decorative items, perhaps even plumbing components, at costs competitive with traditional manufacturing methods.

Cowie says the path to those important new copper and copper alloy products may lie in yet another new CDA development: the technology descriptively called slush casting or semi-solid metal casting. Details of that development are contained in the accompanying article.