Spirit Lines through Copper

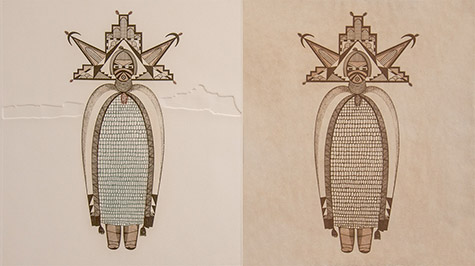

Helen Hardin, Changing Woman, Copper plate etching, 1980.

Photographs courtesy of The James Museum of Western & Wildlife Art /Spirit Lines:

Helen Hardin Etchings

Native American painter and printmaker Helen Hardin had a specific goal in mind when she set out to create a series of copper plate etchings in 1980, just four years before she died of breast cancer at the age of 41.

“I feel this need to do a series of my best works to show the noble women for what they are: intelligent, thinking, hard-working and spiritual,” said Hardin of her etchings that were recently the focus of an exhibition, Helen Hardin: Spirit Lines, at The James Museum of Western & Wildlife Art in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Up until 1980, Hardin had been a painter, but her meticulously detailed linear work was suited to the etching medium, as was evident in the exhibition where all 23 first editions of the artist’s copper plate etchings were on view.

“She was deliberate and controlled with every mark, and her precision was impeccable,” says Emily Kapes, Curator at The James Museum. “She produced some of her very best work in those last years, with thoughtful compositions and intricate layering.”

Accompanying the prints in the exhibit were select copper plates used to make Hardin’s images, as well as an exploration of the etching process. In this traditional form of printmaking from a metal plate, typically copper, the design is incised by acid or mordant.

First, the copperplate is coated with a waxy ground that is acid-resistant to create the etching ground where the design is drawn with a sharp tool. The plate is then dipped in a bath of nitric acid or Dutch mordant, which eats away the areas of the plate that aren’t protected by the ground, which forms a pattern of recessed lines. The lines hold the ink and when the plate is applied to moist paper, the design transfers to the paper, making a finished print.

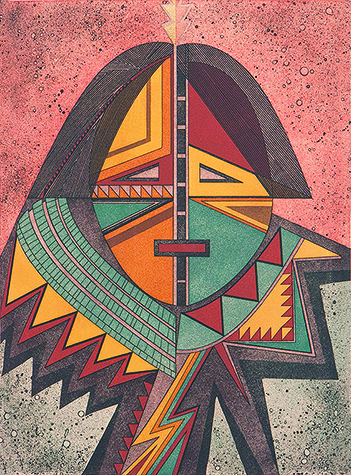

Helen Hardin, Messenger from the Sun, 1980 Etching

Helen Hardin, Messenger from the Sun, 1980 EtchingThe James Museum of Western & Wildlife Art / Spirit Lines:

Helen Hardin Etchings

The title Spirit Lines references etching lines as well as family lines to reference how artistic traditions are often passed down through families. In addition to featuring Hardin in the exhibit, Kapes included art by other Native women with ties to Hardin through family or Santa Clara heritage.

“The artists include Hardin’s mother, Pablita Velarde and Hardin’s daughter, Margarete Bagshaw,” Kapes says. “It’s powerful to see three generations of Native women artists represented together.”

Hardin helped break stylistic boundaries in Native American art with the development of her modern, geometric compositions, at the time when she rose to fame in the 1970s as a young Native woman in a male-dominated art world.

“Her Santa Clara heritage played a prominent role in her art, with a combination of representational and abstract imagery to express elements of her identity,” Kape says.

Kape feels Hardin helped pave the way for stylistic experimentation as one of the first Native women artists to receive the prominence that she did, which in turn inspired many younger artists. Had she lived beyond the age of 41, Kape believes she would have continued to push herself as an artist in painting and printmaking.

“She had so much she wanted to say through her art,” Kape says. “Even before she found out she had cancer, she worked to produce art with such focus and urgency.”

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Spirit Lines through Copper

- The Legacy of Copper Enameling

- The Multi-Faceted Work of Connie Campbell

- Polich Tallix Brings Bronze Back to the Oscars

- Rare Bronze Dalí Exhibit Opens at Aspen’s ChaCha Gallery