Bronzed in Triumph and Tragedy

Jennifer Frudakis-Petry in her studio where she is currently working on a

Jennifer Frudakis-Petry in her studio where she is currently working on a sculpture of Fredia "The Cheetah" Gibbs.

Photograph courtesy of Jennifer Frudakis-Petry.

A moment in time captured at the height of the ability of an individual is just one part of the equation when sculptor Jennifer Frudakis-Petry sets out to create her bronze works of art. Whether depicting an accomplished sports figure, renowned chef or beloved philanthropist, the rest of the equation involves an intentional elevation of the work that is necessary in producing its unseen factors.

“There is more going on than meets the eye that gives it life, a spirit and is an inspiration when you look at it,” Frudakis-Petry says. I try to push it to a higher level, to something that is ideal and has motion, action, and a little bit of inspiration.”

Frudakis-Petry explained the way she goes about achieving this -- the ability to exceed a static representation - is centered on something she learned from her father, the late internationally-known sculptor, teacher and mentor, EvAngelos William Frudakis, when she trained with him at his art academy, Frudakis Academy of Fine Arts, in Philadelphia.

“It’s not just realism for realism’s sake,” she recalls him saying. “You want to find the abstract design that is the essence of the aesthetic that gives it life.”

Sculpture work in progress.

Sculpture work in progress.Photograph courtesy of Jennifer Frudakis-Petry.

Her father was also the one who always told her that if she was going to pursue a career in the arts, that it was up to her to make it a career.

“You are constantly juggling balls and it’s never an easy path,” Frudakis-Petry says. “While I had a natural ability, I had to work very hard and train and learn, and make many failures before any successes.”

Her mother, the late Virginia Parker-Frudakis, an accomplished painter, suffered from the challenges associated with a profession in the arts, which greatly impacted Frudakis-Petry’s life at just seven years of age.

“She succumbed to alcoholism and we lost her,” Frudakis-Petry says. “The loss of my mother was her career choice -- it is demanding and difficult. It was difficult back then for women to balance career and family when having a career as a woman was less accepted.”

Despite witnessing triumph and tragedy associated with the profession firsthand, Frudakis-Petry’s unwavering love of the arts solidified her personal path.

“In a way, I was coming to this on my own,” she says. “At the same time there was influence from my parents in that they both had successful careers in the arts, but they didn’t try to influence me.”

During the summers as a teen, Frudakis-Petry took adult classes in sculpture at her father’s academy, which prepared her for attendance at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts after graduating from high school.

“I didn’t get preferential treatment,” she says of the summer classes, despite her father serving as her teacher. “It was all adults and it was very serious.”

While she declared painting as her major in college, professional opportunities centered on sculpture proved more abundant after graduating.

“I loved both painting and sculpting equally, but I felt more comfortable sculpting -- I like working tactilely and felt very comfortable with the medium,” she says.

Before centering her profession on commissioned work, Frudakis-Petry spent three years in New York City working at Chalk & Vermilion Fine Art where she made sculptures from lithographs by the late artist and designer known as Erté.

Regardless of the source of her work, Frudakis-Petry takes the same approach irrelevant of any passion for or interest in the subject at hand. While she has the luxury of being more selective with her work these days, that wasn’t always the case.

“Your opportunities come to you and you can accept them or not,” she says. “Having been a single mother of two kids, I didn’t have the luxury of saying, ‘that’s not my thing’.

She has also been very flexible in her approach to her work, which has contributed to her ability to have a profession in the arts for almost 40 years.

“I didn’t stick with my own ideas and specific type of work,” she says. “I also teach sculpture at the Wayne Art Center and worked with commissions that were more commercial -- I even did garden sculptures.”

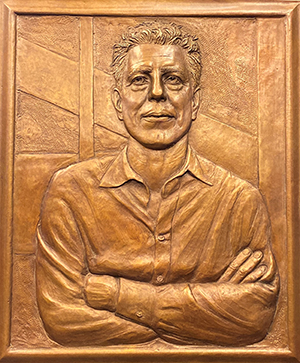

Bronze relief of Anthony Bourdain by Jennifer Frudakis-Petry.

Bronze relief of Anthony Bourdain by Jennifer Frudakis-Petry. Photograph courtesy of Jennifer Frudakis-Petry.

Since 2014 Frudakis-Petry has been the go-to sculptor to make plaques for the Culinary Institute of America in both New York City and Napa Valley, California, each having their own galleries with the one in New York devoted to famous chefs and the one in the Napa Valley centered on wine connoisseurs.

“I was asked to do a plaque for Anthony Bourdain,” she says. “Whenever they need a sculpture, I get to do them.”

The same went for the Philadelphia Flyers Hockey Hall of Fame where she was their go-to sculptor for ten years.

“I love sports, but I’m not a fanatic,” she says. “Anything that comes up that I get a commission for, it doesn’t just stop at the subject matter or narrative.”

She focuses on the person, not the sport, when doing her work. Take for example, a sculpture she made of Pro Football Hall of Famer Emlen Tunnell, now on view at a park named in his honor in his hometown of Radnor Township, Pennsylvania, that began with her doing extensive research.

“There is so little known for all he has accomplished,” she says of Tunnell. “He rose at a time that was very difficult for a black American and he went beyond any expectations, he was a WWII hero and saved two people’s lives on two separate occasions.”

These are the very details Frudakis-Petry amasses about an individual that enables her to have a better understanding of them beyond their sport, which gives her the ability to encapsulate the essence of their being in her work.

“What that individual is and how their position in their sports works and what they do -- it affects the movement of the pose and the action -- it comes from an understanding of the abstract,” she says.

Frudakis-Petry describes how there is an aesthetic to what you can do with art that goes beyond the narrative of the subject matter.

“The action, that movement, the way he might hold a ball or the way a person stands that is an athlete of that particular sport,” she says, of some of the factors.

She takes spatial dynamics into account when strategizing her artistic interpretation of the subject at hand.

“It is planes moving in space that make it look like motion that is frozen in time,” she says.

“That is the spiral effect you get when something is moving to create an emotion and a response to that emotion.”

With a lead time of eight months to a year for a sculpture that is over life-size, Frudakis-Petry first starts her process by making a small-scale 24” model in clay at her studio located at her home in Southeastern Pennsylvania.

“I use an oil-based clay that is malleable and never dries out,” she says.

The next part of the process involves spending six months putting detail in a foam core enlargement before the foundry starts the three to four month lost-wax casting process. Frudakis-Petry has used Laran Bronze foundry in Chester, Pennsylvania since the 1980s.

Jennifer Frudakis-Petry, in coral dress, at the unveiling of the bronze

Jennifer Frudakis-Petry, in coral dress, at the unveiling of the bronze Emlen Tunnell sculpture.

Photograph courtesy of Jennifer Frudakis-Petry.

"The foundry can enlarge your small-scale piece to whatever you want and mill it out in styrofoam for you,” she says. “It’s a huge time saver and it’s much better than building a heavy armature.”

Since technology these days enables one the ability to simply scan a photograph that can be used as the foundation for any sculpture, Frudakis-Petry discusses why sculptors are still in use and have value.

“That abstract movement and space and the aesthetic you don’t get, and that’s why it’s worth it,” she says. “These are things you just don’t get from scanning a photo and getting a 3D image that the artist puts into it and that’s what sets it apart.”

Her latest commission with an unveiling set for the near future is a sculpture of Fredia “The Cheetah” Gibbs, a former professional martial artist, kickboxer and boxer.

“She is a world-champion kickboxer from Pennsylvania,” Frudakis-Petry said, adding that given it’s a woman sculptor making a sculpture of a woman athlete, both from male-dominated professions, makes this project have special significance to her.

Frudakis Petry’s work today reflects her preference to focus her work exclusively on people who are making a difference in the world.

“I want to keep them in the public for decades to come and capture who they are in the piece,” she says. “That is what motivates me now.”

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Bronzed in Triumph and Tragedy

- Copper Art Classes Move Online

- Classic Copper takes Root in the Garden

- The Lasting Bronze Legacy of Dr. Richard Bergen

- Colleges Get Creative to Bring the Studio Experience Home for Copper Printmaking Students