Frank Stella: Copper and Canvas Converge

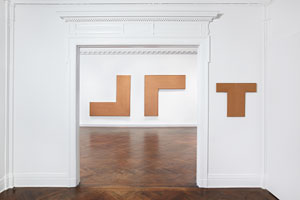

Copper paintings by Frank Stella on display at L&M Arts.

Copper paintings by Frank Stella on display at L&M Arts. Photograph courtesy of Leila Saadai

A recent exhibition of the great American painter, printmaker and sculptor Frank Stella at the L&M Arts Gallery in New York City gave viewers a rare glimpse into the artist’s copper work, which some say helped shape the Minimalist Art movement.

On display from April to June, Frank Stella: Black, Aluminum, Copper Paintings featured fifteen pieces, including five of Stella’s copper paintings from 1960-1962. Unlike his American contemporaries, Stella marked the beginning of his career with minimalist abstract paintings that according to Jennifer Buonocore, Exhibitions Associate at L&M Arts, “astonished the public” when four of The Black Paintings were first on public display at the Museum of Modern Art in 1959 as part of the Sixteen Americans exhibition.

Stella received immediate recognition from the exhibit and, “Over the course of the next few months, Stella executed the Aluminum and Copper Paintings with the same methodical rigor,” says Buonocore, many of which would become the focus of Stella’s first two solo exhibitions in 1960 and 1962 at the Leo Castelli Gallery.

In his 20’s, having recently graduated from Princeton University without even a one-man show under his belt prior to the MoMA exhibit, Stella’s early work was initially summed up by critics as being “unfeeling, cold and intellectual”, according to the artist in a 1972 filmed interview with William Rubin, who was the director of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art. “They seemed to seem that way in the context of 1959-1960,” Stella said of the initial perception of his early work.

In time, the same paintings were heralded as paving the way for Minimalism.

Frank Stella at work.

Frank Stella at work. Photograph by Ugo Mulas

In Rubin’s introduction to Stella he described how he was among a small group of painters in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s who created an abstract painting of equal force and power to “the best of Abstract Expressionism” however, was very different in character.

Rubin said the work “in a sense reacted against the action conception of abstract expressionism -- It’s a kind of more classical, more controlled art.”

Now, sixty years later, as evidenced by the focus of L&M’s exhibit, Stella’s Black, Aluminum and Copper Paintings are getting some time to bask in the limelight again, although this time with their place in the history of art solidified.

“I found the period as the world does – a really special moment in 20th century art,” says Robert Mnuchin, a curator and founder of L&M Arts. “It would be a broad acceptance of the view that these pictures are very special and important.”

Mnuchin emphasizes The Black Paintings were the best known of the three series and the most important of Stella’s work in that period.

“The coppers were not as well known,” he says. “In having an opportunity to see them, they really stood out as being elegant and fresh and very important paintings. The respect for the copper pictures just went up a notch.”

In L&M’s exhibition, Mnuchin enjoyed seeing how the copper work looked in comparison to the aluminum and black pieces.

Black painting by Frank Stella.

Black painting by Frank Stella. Photograph courtesy of L&M Arts

“If anything was a little bit of a surprise to the public and to me, it was how elegant and fresh these works looked sixty years later,” Mnuchin says.

Stella’s approach to the canvas during this period was driven by more than his disinterest in representational painting.

“One of the things that I think was in the back of my mind with the paintings that I was making, particularly the black paintings and the aluminum paintings like that, was it was a way to keep the critic’s mouth shut,” Stella says in a radio interview last year with Tom Ashbrook, host of NPR’s On Point. “They wouldn’t have anything really relevant to make in the terms of traditional art criticism.”

In addition, Stella saw the picture-as-object with the works he produced, rather than the picture as representation. He was once quoted as saying, “I would like the paintings to be their own justification, so that anything asked of them would be irrelevant.” Around 1961 he said his works of art were “a flat surface with paint on it – nothing more.”

For his series of Copper Paintings, Stella used copper paint, a liquid alternative to metal sheets that contains alloy flakes mixed into the formula. The end result is a copper finish that can be applied over a variety of surfaces. In the case of Stella, it was canvas.

Greatly influenced by Jasper Johns’s flag paintings, Stella’s technique involved the repetition of stripes or bands in a flat, regulated pattern.

“I wanted to be able to have what I think were some of the virtues of abstract expressionism, but still have them under a kind of control – but not control for its own sake, a kind of conceptual painterly control that I felt would make even stronger pictures,” Stella said in the Rubin interview.

Copper paintings by Frank Stella on display at L&M Arts.

Copper paintings by Frank Stella on display at L&M Arts. Photograph courtesy of Leila Saadai

The Copper Paintings were similar to his Black Paintings, but gave him a wider range of color and influenced his use of shaped canvas.

In the 1972 Rubin interview Stella described how it is not immediately apparent how his paintings are done.

“The first thing you do is see it, I think, and not see how it was done.”

With names like Creede and Telluride, Stella’s copper paintings were named after mining towns in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado.

Mnuchin was no stranger to Stella’s work upon curating the Black, Aluminum Copper Paintings exhibition.

“I’ve known these pictures literally for decades,” Mnuchin says, describing how he became familiar with the works 33 years ago when he was an art collector working as an analyst for Goldman Sachs.

“I owned an aluminum painting,” he says.

While he explained how the works included in the exhibit might have been in previous shows, he emphasized the exceptional experience one gets in viewing them on a smaller scale.

“There has not been an opportunity to focus on their splendor,” he says, up until L&M’s exhibit. “Many get lost in a retrospective.”

With Stella’s exhibit, L&M has stayed true to its focus as a gallery for showcasing outstanding moments in an artist’s career. One of the underlying motivations behind Stella’s show was, according to Mnuchin, the “real historical importance” represented by the body of work of which he referred to as museum quality.

Stella, 76, offered his support in conceiving and organizing the exhibition. Mnuchin describes Stella as being “very, very” cooperative.

“He helped with loans and when it came time to presenting the pictures – how they might work in relationship to one another,” Mnuchin says. “I think he enjoyed being involved.”

The paintings included in the exhibition, dating from 1958-1962, were on loan from: Glenstone; The Menil Collection; The Philip Johnson Glass House; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; National Gallery of Art; Whitney Museum of American Art; the collection of the artist; and private collections.

The many honors and awards Stella has received in his lifetime thus far include: Skowhegan Medal for Painting (1981), The Mayor of the City of New York’s Award of Honor for Arts and Culture (1982), an Honorary Doctor of Arts degree from Princeton University (1984), an honorary degree from Dartmouth College (1985), and an Award of American Art from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia (1985). In 1983, Stella was named to the Charles Eliot Norton Professorship of Poetry at Harvard. In 2009, Stella was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama.

Stella continues to live and work in New York.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Frank Stella: Copper and Canvas Converge

- Shelbyvision: Timeless Celebration of Nature in Brass or Copper

- Gary Magakis: The Warm Comfort of Furniture in Bronze

- Charles McBride White: Sculptor of the Elements

- Cy Twombly's Final Planned Bronze Installation Goes on View at the Philadelphia Museum of Art