Artist Jim Sanborn: Cracking the Code of Copper Art

Kryptos, 1989, Courtyard plaza of CIA headquarters.

Kryptos, 1989, Courtyard plaza of CIA headquarters.Photograph courtesy of Jim Sanborn

As if copper wasn’t mystically beautiful enough, artist Jim Sanborn crafted coded copper art for one of the most high-profile public places in the world: the courtyard plaza of the CIA Headquarters Building in Langley, Va.

It was the 1980s and, to culminate the construction of the expansion to their new headquarters building, the CIA requested project proposals from artists for a centerpiece work of art for the courtyard. Sanborn was granted the prestigious project (and the $250,000 commission), and Kryptos still stands 20 years later---along with its secret.

Sanborn’s Kryptos (Greek for “hidden”) is comprised of four 3/8 inch-thick verdigrised copper panels soldered into a massive 12-foot-high. The patina copper curls and furls out of a chunk of petrified wood. A round pool and fountain sits at its base. But the real crux of Kryptos is the nearly 2,000-letter cut-outs that form four encrypted messages.

“I had to cut them out with a jigsaw,” says Sanborn in a phone interview. “And each letter had to be drilled four times. I went through 12 jigsaws in the course of 2 years – this was before water jets – and went through seven assistants.”

On top of that, letters weren’t just hand-drilled randomly; they were placed into codes. With the help of retired CIA cryptographer Edward Scheidt, Sanborn embedded four messages into the aptly named Kryptos, which has turned into a cultish obsession for code-crackers worldwide. There’s even a Kryptos Wiki, a Kryptos Yahoo Group and a website formed by Elonka Dunin. It’s said that hundreds have e-mailed him, called him – even unexpectedly dropped in at Sanborn’s home in the D.C. area.

Author Dan Brown also mentioned Kryptos in his wildly popular “The Da Vinci Code” and “The Lost Symbol,” but without Sanborn’s blessing. “And, most importantly, he tried to bend the meaning of my work to his religious/Masonic plot line,” says Sanborn.

So far, three out of the four messages – 768 characters – were solved by ambitious sleuths by 1999. The fourth, embedded in 97 characters, has yet to be solved. And Sanborn wasn’t about to divulge the secret to Copper in the Arts; we can only go by what Sanborn revealed to the rest of the world in The New York Times in November 2010 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of his sculpture: BERLIN. “I felt as though would-be crypto solvers needed some encouragement,” says Sanborn, “and that I needed to do something that marked the 20th anniversary of the dedication of Kryptos.

A Comma, 2004, on copper panels.

A Comma, 2004, on copper panels.Photograph courtesy of Jim Sanborn

He’s taking guesses online via www.kryptosclue.com; so far, no one has gotten more than two correct letters. Two slabs of the Berlin Wall, incidentally, which came down a year before Kryptos was dedicated, also sit at CIA headquarters.

With the left two panels serving as the “message hosts,” the right two panels feature the key to the code. Each is encrypted differently and at different lengths. All contain misspellings – an added challenge from Sanborn.

The first message was a poetic line written by Sanborn: “Between subtle shading and the absence of light lies the nuance of iqlusion.”

The second message translates into: “It was totally invisible. How’s that possible? They used the earth’s magnetic field. The information was gathered and transmitted undergruund to an unknown location. Does Langley know about this? They should: it’s buried out there somewhere. Who knows the exact location? Only WW. This was his last message. Thirty eight degrees fifty seven minutes six point five seconds north, seventy seven degrees eight minutes forty four seconds west. Layer two.”

And the third is a twist on a portion of Egyptologist Howard Carter’s diary that captures the opening of King Tut’s tomb in 1922: “Slowly, desparatly slowly, the remains of passage debris that encumbered the lower part of the doorway was removed. With trembling hands I made a tiny breach in the upper left-hand corner. And then, widening the hole a little, I inserted the candle and peered in. The hot air escaping from the chamber caused the flame to flicker, but presently details of the room within emerged from the mist. x Can you see anything? q”

With his innate talent for codes, Sanborn has gone on to sculpt a plethora of text encoded copper sculptures at major institutions, from college universities to museums, throughout the United States.

“My father worked at the Library of Congress as director of exhibitions and my mom was a library researcher,” he says.

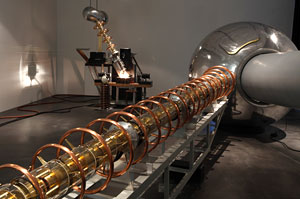

Terrestrial Physics, 2007-2010

Terrestrial Physics, 2007-2010Photograph courtesy of Jim Sanborn

Since Kryptos, the construction has evolved into a much more streamlined process, with research assistants to help with the historic- and linguistic-related projects. He then works with a photography company, who lays out the pieces on a computer and a water jet company in the Midwest that cuts out the text in Sanborn’s customized typefaces before he assembles and fastens the pieces and finishes it off with a layer of patina. International texts like Chinese characters, he says, can be quite difficult.

Copper sculpture standouts include Rippawam, rolled copper with Native American text standing on the University of Connecticut campus, and A Comma, A, in front of the library at University of Houston.

Sanborn chooses copper as his medium of choice because of the metal’s durability.

“When your client knows you’re working with copper or bronze, they know the artwork is forever,” says Sanborn. “I had a foundry for eight years, where we poured bronze metal. I also taught at the foundry and did casting, but had never used it for my own work.”

That soon changed, and now the D.C. native, with a bachelor’s in art history and sociology and a master’s in sculpture, has set his own standard code in copper sculpture. He recently completed Terrestrial Physics for MCA in Denver and plans to install another commissioned copper sculpture in a couple weeks in Bethesda, Md., that includes quotes from Thomas Jefferson.

“I’m hoping my work says a variety of things,” says Sanborn. “I consider myself a nonfiction artist … I don’t make a sculpture based on form; the content is sometimes more important than the meaning of work. The work I do that is site-specific work is based on the mission of the agency I’m doing it for. My gallery is for myself and I can put into each work whatever I want to put into it.”

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Artist Jim Sanborn: Cracking the Code of Copper Art

- SLD Designs: Unique, Original, and Always Adapting

- The Copper Panels of Artist Bruce McCall

- Sweet Freedom Designs: Reborn through Copper

- Getty Museum Presents Ancient Cambodian Bronze Masterpieces from the Khmer Empire