Getzen: The Music of Metal

The original Getzen Company, Inc. shop was bornin a converted dairy barn behind the Getzen family residence in Elkhorn, Wisconsin.

The original Getzen Company, Inc. shop was bornin a converted dairy barn behind the Getzen family residence in Elkhorn, Wisconsin.Photograph Courtesy of Brett Getzen

Since 1939, musicians around the world have credited the Getzen Company for creating some of the finest brass handcrafted trumpets, cornets, trombones, and fluegelhorns in the industry.

In a business dominated by huge corporations, staying afloat for so long is no minor feat, and the business has experienced a number of twists and turns as it was passed down through four generations. Today, the name Getzen continues to be synonymous with fine brass instruments, and each piece is handcrafted and made in the United States.

Founded by Anthony Getzen as a musical instrument repair business with just four employees, the company began producing its own line of trombones in 1946. By the end of the 1950s, Getzen also made trumpets and cornets and employed more than 80 people. In the years that followed, the company was sold, enjoyed considerable growth, and experienced a devastating fire. In the meantime, the Getzen family started a new instrument repair business called Allied Music while the company bearing its name was run by others.

When the Getzen Company was sold again, production and design changes lowered the quality of its instruments to such a degree that the company landed in bankruptcy court in 1991. This was a golden opportunity, however, for the Getzen family to buy the company and regain control of its namesake. The founder's grandsons - Tom and Ed Getzen - were then faced with the uphill battle of restoring the reputation of the Getzen name. Today, the company is run by two of Tom's sons and is again well-respected as a manufacturer of high quality musical instruments.

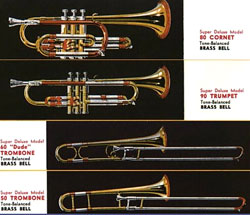

Getzen catalog from the 1950s

Getzen catalog from the 1950sPhotograph courtesty of Brett Getzen

Brett Getzen, the company's Special Projects Manager (a title that he says is largely a "catch-all"), calls Getzen a "medium-sized" company in the industry. On one side are custom makers who charge five figures for their instruments, and on the other side are mass producers that build much cheaper instruments. "We do somewhere between 10,000-15,000 instruments a year depending on the year," he says. A company like Yamaha makes that many instruments every quarter.

Unlike the corporate giants, however, Getzen's production is based much more on hand labor, and this allows them to create instruments with more individuality compared to those that are created entirely by machines.

"There are certain things that automation is good for, but one of the biggest traits of an instrument is character," says Getzen. "You try to build all of them as close together as you can get, but brass and nickel are temperamental beasts. So, no matter what you do, everything is a little bit different. That's the character of the instrument. A guy might play five of the exact same model of trumpet, and one of them to him is better than the rest. Another guy will like a different one."

What accounts for this difference in character from one instrument to the next? It has to do with the tempering and hand-working of the metal. "When that becomes an automated process, you lose all of that character, and what ends up happening is that people describe their instruments as mechanical sounding," Getzen says.

Of course, machines are still required in the making of any musical instrument. "There's some machine work done on everything," says Getzen. The bells in the instruments are "hand-spun," however. "They're on a lathe, but it's an actual person holding the tool that's doing the spinning," he says. "Is that technically all by hand? No, but compared to everyone else in the industry that has an automated machine to do it all, that's considered 'by hand.' All of our soldering is done by hand. All of the brazing is done by hand. Our single biggest cost is labor. Material costs of the trumpet, you're talking - depending on the cost of brass and nickel - probably $25. Everything else is labor, so it's very, very labor-intensive."

Some of the company's bells are "hand-hammered." From a single sheet of brass, they are formed into a cone by hand. Then, they are spun and hammered. They also have to be annealed seven or eight times because the brass hardens so much during the process. It takes about seven times longer to build a hand-hammered bell, so these bells are used in the more expensive professional instruments. They give an instrument more character, individuality, richness, depth, and overtones.

Getzen instrument maker at work

Getzen instrument maker at workPhotograph Courtesy of Brett Getzen

When the company hires someone new, it is a considerable investment because everyone has to be fully trained. Getzen says that it takes ten months before new employees are proficient at a task and 1-1/2 years before they become profitable employees. When people struggle to learn a particular job, the company trains them in a new task to see if they have more of a facility for one job over another. Getzen employs about 100 people total with 78 working in the factory.

While the majority of the metal used in building the instruments is brass, nickel is often used where extra strength is needed, such as for pistons and inner slide tubes. The nickel is then usually plated with nickel-silver. Different shades of brass are sometimes used as well. A red brass which contains more copper, for example, produces a warmer sound.

The Getzen Company has an affiliated organization called Edwards Instrument Company which makes higher-end, specialty-type instruments. "We're Chevy, and they're Cadillac," Getzen says. Edwards provides musicians with a near-custom instrument for less money and less time than a fully custom instrument. "The way Edwards works is that everything is designed on what's called a modular basis," Getzen says. "You can take off a certain part and change things around…. We combine the possible options of different thicknesses of the metal of the bells, different tempering, and different finishes. There are 1.5 million possible trumpets that Edwards can make."

Edwards works with musicians to fine-tune an instrument for their personal taste. The company's personnel start with a certain kind of lead pipe and bell, and the musician might say, "I wish it sounded a little bit darker." The technicians at Edwards know what parts to change to get closer to the sound the musician is after. "It's almost like à la carte trumpet and trombone-building," Getzen says.

Getzen's Piccolo Custom Trumpet 3916

Getzen's Piccolo Custom Trumpet 3916Photograph courtesy of Brett Getzen

While Edwards sells directly to the customer, the Getzen Company only sells wholesale to dealers. Still, Getzen sometimes works with musicians to design its instruments. One such musician was Doc Severinsen, who was the trumpet player on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson for many years. Severinsen was actually part of the company in the 1960s and joined again in 2000 for a few years. At that time, the Getzen Company built a special trumpet for him, which it still manufactures, although the trumpet no longer carries Severinsen's name. "Several of our models have been the same for 40 years," Getzen says.

A music professor from Michigan State University has also helped the company with design. The process is often a matter of trial and error. They combine different elements to simply see what will happen. Luckily, several of their employees are good musicians, so they can try out the instruments to see if the experiments work. The company maintains a line of about 45 instruments exclusive of what Edwards makes, including a piccolo trumpet and capri horns.

Musician Kiku Collins, who has played with the likes of Beyonce Knowles and Michael Bolton, has been playing a Getzen 3001MV trumpet and a Getzen custom fluegelhorn for about three years. Of her trumpet, she says, "I've never had anyone pick it up who didn't love it," and she calls her fluegelhorn "the most beautiful fluegelhorn I've ever played."

The Getzen company especially prides itself on maintaining little variance between its professional line instruments and its student-level instruments. The trend today, as is the case in most industries, is to send more and more production offshore, lowering both quality and price, but the Getzens refuse to do that. "On one hand, our student-level instruments are vastly superior to anybody else's," says Getzen. "At the same time, they're more expensive." This can be problematic when parents fail to understand the difference between a $200 instrument and an $800 instrument.

That difference is substantial, however, according to Getzen. "The biggest problem with the cheaper instruments is that they just don't play right," he says. "So now, you're trying to teach a kid how to play, say, a trumpet that doesn't perform right. A lot of them don't play in tune and are harder to get a good sound out of. It's harder for kids to learn. Generally, they get frustrated and quit sooner." Students often think their inability to play well is their own fault when it's actually the fault of a poorly made instrument. In fact, a school district in Minnesota increased its trumpet-player retention by 75% after it switched to Getzen instruments.

Getzen's founder and his brother were both in the musical instrument business prior to starting the Getzen Company. Only a couple of family members have "opted out" of the industry. Several members of the family are also amateur musicians. Brett Getzen grew up across the street from the factory and began doing some work for the company at the tender age of 11. "We always joke that it's in the blood," he says. "You can't get away from it."

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Getzen: The Music of Metal

- Sandy Jackson Fine Art: Reflecting Life Through Copper

- Artterro: Handcrafted Copper Kits for Kids

- Pete McCaskill: Inspired by Copper

- Herb Alpert Bronze Exhibit at Ace Gallery