Nicholas Toth Dives Deep into His Grandfather's Art

Copper diving helmet

Photograph courtesy of Nicholas Toth

Since 1905, Tarpon Springs, Florida, has attracted Greek sponge divers who walked along the bottoms of the sea floor off the Gulf Coast, usually with the aid of a brass diving helmet, gathering sponge for a thriving market. One of the city's earliest diving helmet artisans, Anthony Lerios, came to the area in 1913 and set up shop not only as a maker of handcrafted diving bells but as an engineer who could make metal parts for the sponge diving boats in the shipyard next door. His grandson, Nicholas Toth, is carrying on the tradition of fashioning handcrafted diving helmets made from copper, brass, and leather, using old-world techniques with wood patterns, cast iron mandrels, lathes, milling machines, and other specialized tools that Anthony Lerios devised.

"Sponge diving was done by naked divers, holding a flat stone called a bell stone (which is a flat piece of rock with a hole at one end with a rope tied to it), and jumping off the sponge boats," said Nicholas Toth. "They would go down over 100 feet, let go of the rock, and pick as many sponges they could off the bottom, holding their breath, push off the bottom, go up to the top, and unload the sponges." In the 1840's a Greek who had worked for Siebe & Gorman, a British diving helmet company, received a set of diving gear on his retirement. He brought that back to the Dodecanese and the village blacksmith started copying the diving helmet, using copper, brass, and leather.

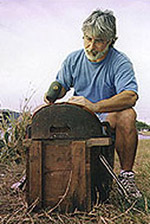

Nicholas Toth forming the breastplate on a cast iron mandrel.

Photograph courtesy of Nicholas Toth

Lerios, who was born in Kalymnos, grew up hearing stories of Greek sponge divers though he himself lived and was educated in Istanbul, Turkey. He worked at the shipyards in Istanbul, building huge steam engines for oceanliners, and was made manager of the shipyard at 22. To escape conscription into the Turkish army to fight fellow Greeks in 1913, he hopped a freighter and headed for New York and eventually moved to Tarpon Springs to be with his father and brother who had settled there in 1905.

Lerios quickly made a name for himself as an engineer, repairing the engines for sponge boats, often handcrafting parts. "There were no catalogs to order things out of," Toth said. "He made propeller shafts, stern bearings, stuffing boxes, propeller guards, dive ladders, compressors, a whole system with holding tanks, and all the pulleys and all these ancillaries that went into creating an operating boat." Lerios also made diving helmets, and, he made them well. Lerios soon became known for his exquisitely handcrafted diving bells, which have become an iconic fixture in Tarpon Springs and beyond.

"One of the first things my grandfather did when he came over in 1913 was put on the diving gear and go diving just to see what the helmet needed, if it needed any modifications, or if there was anything he could do to improve on it. That was just how my grandfather was," recalls Anthony.

Lerios improved the diving bell by creating a protruding face plate that was angled slightly down so that divers could have a clear and undistorted view of the ocean floor. He also added the port on the top so that the diver could look up easily and keep the boat in site. This was important because sponge boats do not anchor but keep moving and sort of "fish the diver" along the bottom. If a diver isn't aware, his air hose could get tangled in the boat's propeller. Another modification Lerios made was moving the air exhaust valve to the side of the helmet instead of in the back. Since the diver must keep tapping the valve as he breathes, side location allows the diver to keep his orientation toward the ocean bottom where the sponge are. In addition, Lerios also tapered the breastplate in front so that the diver has greater range of motion.

Creek sponge divers

Photograph courtesy of Nicholas Toth

Lerios brought an unparalleled level of craftsmanship to the sponge diving industry and became an iconic fixture in Tarpon Springs. Today, you can find an image of his diving bell on the city's welcome signs.

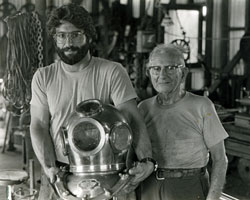

Nicholas Toth grew up in his grandfather's dive shop. When he was around 10 or 12, Lerios began to show him how to hold the tools and work the lathe by putting his bigger hands over the boy's and allowing the youngster to learn the feel of the machines. He also did that with placing the gauges in the helmets, old hands over young hands, so young Toth would know exactly how these pieces fit and how far to tighten them.

Since 1979, when Toth starting working in earnest with his grandfather, he has used large 3' x 10' sheets of copper he gets from a supply house. "You cut out a piece 20-something inch long by 16 inches wide. Out of that rectangle, you create an egg shaped, 30 inch circular piece of copper," Toth said. That becomes the breastplate, which is hammered out on a cast iron mandrel that is over a 100 years old with a wooden hammer and pegs. Both pieces of the helmet fit together on an interrupted threading, with leather seals on the plate glass portholes that close like compression fittings, creating water-tight seals. Though the elements are simple (copper, brass, plate glass, leather, and solder), the result is not only a serviceable, working diving helmet but a work of art.

Nicholas and his grandfather Anthony Lerios.

Nicholas and his grandfather Anthony Lerios. Photograph courtesy of Nicholas Toth

"As an artist, I want to express myself in a different way and part of it is to expand the demographic that I expose my work to," he said.

Toth continues to make helmets for a few local divers, and is currently exploring new markets, receiving orders from diving clubs and individuals across the globe. Continuing in his grandfather's methods, Nicholas Toth, Master Helmet Maker is determined to make his own mark.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Nicholas Toth Dives Deep into His Grandfather's Art

- Phoebe Adams Fine Art: Finding the Balance

- Gary Rosenthal Collection: Contemporary Judaica Art Rooted in Tradition

- Rob Koehl: Serendipity Through Copper

- Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University Receives Two Major Bronze Sculpture Acquisitions