The Revived Art of Brass and Bronze Marine Hardware

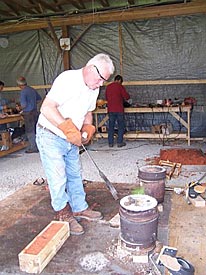

Sam Johnson casting marine hardware at the Wooden Boat Museum

Sam Johnson casting marine hardware at the Wooden Boat MuseumPhotograph by Sam Johnson

"Nobody went sailing for pleasure until the middle of the 19th century," according to John Summers, Chief Curator at the Antique Boat Museum in Clayton, New York. By the time yachting started to grow in the 1800's, there were all sorts of commercial builders. "There were several really substantial foundries that had 200 or 300-page catalogs."

Most of the boat builders ordered hardware from these catalogs, and if you look at plans for a boat of that era, you're likely to see the manufacturer's code number for the hardware. This doesn't mean, of course, that the hardware wasn't beautiful and well-made, but it wasn't one-of-a-kind.

"However beautiful the windshield brackets were, they were probably one of 950 pairs," adds Summers.

It was the pattern-makers in the factories who were the true artists, but they weren't revered as such. They were anonymous workers who created great designs, many of which became their company's trademarks in the industry. It was the designers of the boats themselves who got the attention, however.

On large yachts, for example, these pattern-makers might have created decorative castings like the shape of a fist on the end of the boom or an elaborate piece on the end of the tiller. Most people in the know would say that Nathanael Herreshoff was the most revered yacht manufacturer of the 19th and early 20th centuries. He created yachts for the wealthy and produced sailboats that won the America's Cup from 1893 to 1920. The Herreshoff Marine Museum in Bristol, Rhode Island contains 60 of the company's original boats, which include especially fine bronze marine hardware.

American Canoe Association award medallion

American Canoe Association award medallion Photograph courtesy of Emmett Smith, Antique Boat Museum

Today, Roger Winiarski of Bristol Bronze in Rhode Island specializes in reproducing Herreshoff's hardware and has even taught a seminar at the International Yacht Restoration School in Newport, Rhode Island to teach others this artistic take on marine hardware. He maintains 800 standard items in his catalog, and is the only manufacturer who produces many of these pieces which, in most cases, haven't been made since World War II. Winiarski has also made more than 200 custom pieces for such clients as Dennis Conner (four-time America's Cup winner), who is in the process of restoring a 1925 wooden boat.

Winiarski uses a lost wax casting process, also called investment casting, that allows for such precision that if he leaves a scratch on his first piece, it will reproduce on every duplicate.

"What I'm trying to do," Winiarski says, "is make the old fittings but use new metallurgical techniques that are more modern to make the fittings more precise each and every time." He says that most of today's mass-produced marine hardware is subpar by comparison to vintage hardware. "They don't look good, they're not made in the proper metals, and no two of them match. And boat owners hate that, especially people who are restoring beautiful old classic boats."

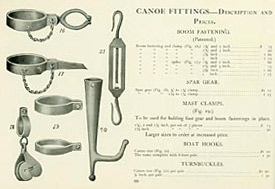

Another craft that frequently included beautifully made hardware were sailing canoes. While bronze was required to withstand the corrosive abilities of salt water, these small fresh water canoes were fitted with lightweight brass hardware that was called "canoe jewelry" because it was so elaborate. The size of the boats meant that the metal work had to be very delicate.

1904 sales catalog of J. H. Rushton, a well known builder of small boats from Canton, NY

1904 sales catalog of J. H. Rushton, a well known builder of small boats from Canton, NY Photograph courtesy of Emmett Smith, Antique Boat Museum

"Most of these [canoes] were owned by fairly well-off middle or upper middle class people, so it was very yacht-like in a tiny way, which made it more precious," says Summers, who ads that the canoes were quite expensive, costing about as much as a car.

Adirondack guide boats also often had exquisitely detailed brass or bronze hardware. Used for rowing, these boats are lightweight enough to be carried on the head as people move from one lake to another. Some of these boats are displayed at the open-air Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake, New York (www.adkmuseum.org), and Lory Wedow of Blue Mountain Metal Arts in Brocton, New York specializes in sand castings of ornate oarlocks for guide boats.

While bronze was common on salt water craft, nickel-plated brass was most common on fresh water craft in the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century. You might see hardware on these boats today that has a natural brass color, but this is only because the nickel plating has worn off over time. In fact, if you enter a fresh water boat in a boat show, you might be penalized for plating the hardware in chrome rather than the authentic nickel. So, why isn't copper used more often on boats? Since it's a more malleable metal, it's perfect for fastenings such as nails, but it isn't generally used for other types of marine hardware.

Downstairs brass fireplace on La Duchess, 110 foot houseboat owned by George Boldt

Downstairs brass fireplace on La Duchess, 110 foot houseboat owned by George BoldtThe trend among amateurs toward restoring and building wooden boats is one that continues to grow.

"Beginning in the early 70's, people started at least in the U.S. to carry out a revival of wooden boat building," Summers says. "One of the ways they did that was to go back to smaller, more recreational-style boats and to teach boat building to amateurs, not professionals."

The Mystic Seaport Museum and the Antique Boat Museum helped to start this trend. "When it began, it had a very live in a teepee, eat granola, back-to-the-land-ish, do it the hard way on purpose kind of thing to it," he says. Today, the amateur builders are producing marvelous boats even though they don't make them professionally. "They're not necessarily amateur in their skill level. They just don't do it for a living," says Summers.

Marine hardware is still mass-produced, but the majority of it is in aluminum and stainless steel to accommodate fiberglass boats, which makes it harder to find bronze and brass hardware. If the boat is handmade rather than manufactured, mass-produced hardware often doesn't fit quite right. Certainly, if someone is building a replica of a vintage boat or restoring an antique, finding the proper hardware can be next to impossible unless you cast your own or contact someone like Roger Winiarski or J.M. Reineck & Son in Hull, Massachusetts, who also specializes in reproducing Herreshoff hardware.

"You walk around the flea market at the Boat Show these days, and it's hard to find the piece you want," Summers says.

Detail of brass marine fireplace

Detail of brass marine fireplace Photographs courtesy of Emmett Smith, Antique Boat Museum

Some of the old patterns have been collected in order to build replica hardware, however. The International Yacht Restoration School in Newport, Rhode Island obtained a collection of patterns from a company called Rostand after it closed and sold the patterns to Historical Arts & Casting, a metalwork manufacturer in West Jordan, Utah. When no one pays attention to these old patterns, they often end up as decoration on the walls of seafood restaurants or completely destroyed like the patterns of Merriman Brothers, a yacht hardware company that was based in Boston.

The desire for authenticity has created an increasing demand for custom-made hardware that keeps people like Winiarski busy with orders from all over the world, but the do-it-yourself attitude has more individual builders wanting to learn the art of casting. One such builder is Sam Johnson, who mostly taught himself how to build a furnace, make patterns, and sand cast his own hardware. Today, Johnson divides his time between making custom pieces for other builders and teaching others how to cast their own bronze pieces. He lives on the ship canal in Seattle in a floating workshop that he maintains in a 1932 motor yacht. He teaches sand casting at several locations, including the Center for Wooden Boats in Seattle, the Mystic Seaport Museum, and the Wooden Boat School in Brooklin, Maine. Johnson receives frequent requests to teach in new places.

"I find it enormously amusing that here I am largely self-taught," he says, "and yet, people want me to come all over the place and teach them how to do it."

In fact, Pratt & Whitney, a company that specializes in the design and manufacture of aircraft engines, became fascinated by Johnson's work. Even though this company produces some of the most sophisticated metal castings in the world, they asked Johnson to teach some of their engineers how to do his method of sand casting.

"It's low tech meets high tech," he says. He's quick to mention that it isn't that others aren't capable of teaching. It's just that the majority of people who cast want to make hardware for a living rather than teach others how to do it.

Lory Wedow's bronze sand-casted oarlocks for Adirondack guide boats

Lory Wedow's bronze sand-casted oarlocks for Adirondack guide boatsPhotograph by Lory Wedow

The sand casting process is quite different from the lost wax casting practiced by Winiarski, which requires more steps and can be more expensive. Lost wax casting is usually required to make very complex and precise hardware, but Johnson says that sand casting can accomplish more than you think.

"The old time foundry guys have many, many clever little techniques to convert something that people would say you can't do with sand casting," he says. "Next thing you know, they've shown me how it can be done."

Johnson says that sand casting has been practiced for thousands of years. Brass is an alloy of mostly copper and zinc, while bronze is an alloy of copper and tin. There is no clear line that distinguishes brass from bronze, but the rule of thumb is that an alloy must contain 15% or more of zinc in order to be considered brass. If it contains less than 15%, it is generally considered bronze. He says that one of the best alloys for boat fittings is silicon bronze, which is an alloy of copper and silica that resists corrosion very well. Johnson builds his furnaces in 5-gallon paint cans which can reach 2100 degrees.

"I'm mostly concerned with teaching people how they can do it themselves on the cheap," he says.

Steel and iron require higher temperatures, so those metals cannot be used with these furnaces. While the furnace can be powered by electricity, it will take longer to melt the metal and allow for more oxidation to take place. Therefore, he recommends that the furnaces be powered by wood, coal, charcoal, or gas. Of course, the 5-gallon furnace isn't large enough to create large castings, but Johnson also teaches his students how to make their own patterns. If a large piece of hardware is required, they can make the pattern and take it to a commercial foundry for casting.

The patterns for sand casting can have no undercuts that would prevent removal of the pattern from the sand, but otherwise, patterns can be made of nearly anything. "You can make anything that can go on a boat," Johnson says, such as oarlocks or a bow roller. Withdrawing the patterns from the sand can be difficult, but there are several different methods that he teaches in his courses.

Johnson's course is generally a week long and goes through the entire process from building the furnace to polishing the finished castings. He often manages 10-12 students, including women.

"Eight to 10 students is my preferred number," he says, "because it's really almost a hands-on, individual tutorial."

While Johnson stresses that the process is very safe, it does, of course, require safety gear, including safety glasses, a face shield, heavy cotton pants and shirt, leather work boots, welder's gloves, and additional leather gear on the body. Casting should be done in a well-ventilated area because the furnace produces carbon monoxide and other noxious gases depending upon the type of metal used.

Although bronze hardware originally began as a mass produced process, it is nice to know that there are some bronze and brass artists keeping the legacy of this regal art alive.

Also in this Issue:

- The Revived Art of Brass and Bronze Marine Hardware

- Apprentice and Alchemist: Tanya Garvis

- Sculpting Copper: Movement through Welding

- Rediscovering the Geddy Foundry's Colonial Roots

- The NSS Presents 75th Annual Awards Exhibition