Rediscovering the Geddy Foundry's Colonial Roots

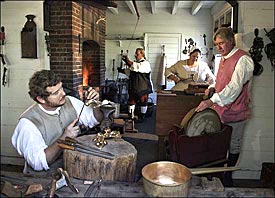

Interpreters demonstrate colonial techniques in Colonial Williamsburg's Geddy Foundry

Interpreters demonstrate colonial techniques in Colonial Williamsburg's Geddy FoundryPhotograph contributed by Karen Mortensen

My husband and I moved from Washington state to Virginia in 2004 and never looked back. Don't get me wrong. I was born and raised in Seattle, I adore Washington-even the side with yellow grass and tumbleweeds-but there's one area where Washington can never catch up to Virginia, and that's colonial and early American history.

Personally, I think the best way to experience this kind of history is through living history museums. And Colonial Williamsburg is like the Disneyland of living history museums, as far as Virginia goes. You get there, drop your jaw, and say, "Honey, maybe we should stay for more than one day."

You know, some people get their kicks in Vegas. I'd rather watch a guy show me how a brass candlestick was made in 1750. And that's exactly what they do today in Colonial Williamsburg at the Geddy Foundry, just like it was done back in the 18th century.

An integral part of the Colonial Williamsburg's business community, the Geddy Foundry legacy began when Scotsman James Geddy Sr. started a foundry behind his home circa 1738. However, only six short years passed until he died suddenly in 1744, leaving his entire estate to his wife, Anne. She was bright and assertive, which was fortunate, considering James had left her with eight children: four boys and four girls.

The oldest boys, William and David, had probably had enough exposure to the business before their father's death, and took over the foundry. In addition to gunsmithing and brass founding, they advertised their services as buckle makers, cutlers, and sword cutlers.

While David may not have been involved in the business after 1751, it's clear that William managed and grew the foundry for more than 30 years. Even William's son, William Jr., became involved as an apprentice.

Sand mold for candlestick and carriage window latches

Sand mold for candlestick and carriage window latchesPhotograph contributed by Karen Mortensen

William and David had a brother named James, who was 13 when James Sr. died. James Jr. became an expert silversmith, and opened a silversmith and jewelry business in 1760. In fact, he bought the family home and lot from his mother, Anne, and set up shop right there. He was known as the finest silversmith in Williamsburg, even repairing two fans for George Washington.

Today, the Geddy Foundry in Colonial Williamsburg stands as a testament to the talent and determination of this artistic family. To preserve the history of brass and bronze casting as both craft and technology, it operates today much as it did more than 250 years ago, except now it welcomes visitors to become part of the experience. A shop master, journeymen, and apprentices create pieces using the same methods employed by the Geddys.

When the Geddy site was excavated in 1968, researchers found a variety of metal artifacts that had been cast, including candlesticks, buckles, and watch keys. Visitors to Colonial Williamsburg see many examples of cast metalwork in the reconstructed foundry, learning about the process from expert historians.

Casting pieces in brass and bronze in colonial times was truly an art-it wasn't production work. Craftspeople at the foundry explain and demonstrate how pieces were designed and made individually.

Each item required its own mold-and mold-making was the most difficult part of the process. In addition to making the mold, many more steps were involved in creating a single piece, all of which required considerable skill and experience.

Visitors to Colonial Williamsburg learn that 18th century founders were generalists, making a wide variety of objects. In fact, it wasn't until the industrial revolution came to America in the 19th century that mass production became the norm in the U.S.

It goes without saying that mass production is here to stay. But it would be a horrendous mistake to lose the skills we once had-to forget how we used to do things. This is why the individuals preserving our artistic and technological history at the Geddy Foundry are so vital.

History isn't just about the shift of world power and politics and wars and dates, although that is all important. It is also about the way art and technology progressively work with or against each other, or put simply, how the creation of a candlestick changes over time. And it's about standing in a hot workshop in Colonial Williamsburg in a muggy July heat wave, thinking, "This is fascinating, but next time, I'll come in the spring."

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- The Revived Art of Brass and Bronze Marine Hardware

- Apprentice and Alchemist: Tanya Garvis

- Sculpting Copper: Movement through Welding

- Rediscovering the Geddy Foundry's Colonial Roots

- The NSS Presents 75th Annual Awards Exhibition