Calder's Brass Jewelry on View

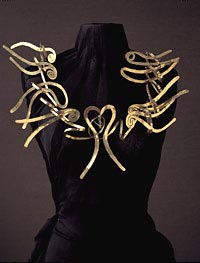

Harps and Heart, sculpted from brass wire

Harps and Heart, sculpted from brass wire Photograph by Maria Robledo, ©2007 Calder Foundation, New York/Artist's Rights Society

Beginning as a child with embellishments to the costumes of his sister's dolls, the American sculptor Alexander Calder (1898-1976) created more than 1800 pieces of jewelry, many using brass wire. Best known for his invention of the mobile, Calder also produced these precious ornaments throughout his lifetime—for his wife, family, artists, friends—and as a more intimate dimension of his monumental art.

The personal nature of his jewelry, and the inspiration it drew from sources ranging from the primitive to the modern, provide insight into Calder's life and art. On view through November 2, the Philadelphia Museum of Art will present Calder Jewelry, the first museum exhibition to examine the jewelry on its own and in depth, as sculpture on a smaller scale. The exhibition, in the Perelman Building, consists of some 100 necklaces, bracelets, pins, earrings, and tiaras.

"Alexander Calder was among the great sculptors of the modern age, and Calder Jewelry offers a rare and delightful occasion to experience-on our city streets and here in the galleries-the artist's infinitely creative imagination at work on both a monumental and diminutive human scale, notably in these astonishing ornaments for the body," says Elisabeth Agro, the Nancy M. McNeil Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Crafts and Decorative Arts.

The metalwork from numerous ancient cultures significantly influenced Calder brass creations. He was attracted to the directness of ancient processes and loved the simplicity of their forms.

Calder necklace, sculpted out of brass wire, ceramic, and string.

Calder necklace, sculpted out of brass wire, ceramic, and string. Photograph by Maria Robledo, ©2007 Calder Foundation, New York/Artist's Rights Society

"When a mobile by Alexander Calder is seen packed in a crate, it is a flat, lifeless object," notes exhibition curator Mark Rosenthal in the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition. "Picked up by its highest element, all of the components take their assigned positions, and the mobile will become animated, three-dimensional, and imbued with motion. A necklace by Calder lives in the same way-inside and outside a crate. The only real difference between the two is that the structure of the mobile, with its rigid metal spokes, creates the breadth of the work of art, whereas the necklace usually depends on the body of the wearer to expand from a static state to fullness. Both works are of a piece and cut from the same cloth of activity."

"Making jewelry was very personal for him, and each piece exists as a unique work," adds Calder Foundation Chairman and Director Alexander S. C. Rower, the artist's grandson. "Some of his gifts for his crowd (of friends) are included here: a brass wire ring enclosing a tri-colored fragment of porcelain for Joan Miró, a gold "P" initial brooch for his wife, Pilar, and a silver brooch of her name for their daughter, Dolores; for Jeanne and Luis Bunuel, a gigantic flower brooch (with shards of colored glass and mirror for petals)."

For Calder's jewelry, the wearer becomes significant both as context and structural support, and the exhibition will be punctuated by enlarged images of people wearing the jewelry, including Calder's wife, Louisa James. Other well-known women adorned by Calder, including Georgia O'Keeffe and Peggy Guggenheim, also suggest the jewelry's popularity over the years.

Following its showing in Philadelphia, Calder Jewelry will travel to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, from December 8, 2008 to March 1, 2009, and the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, from March 31 to June 22, 2009.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Contemporary Furniture Designers Turn to Copper

- Chemistry on Copper: The Works of Cheryl Safren

- Pomegranate Metals: A Family Legacy

- Uncovering the History of Coppertown USA

- Calder's Brass Jewelry on View