The Guggenheim Legacy: From Copper to Contemporary Art

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City Photograph by Finlay McWalter

The next time you stroll through the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, on Fifth Ave., in New York City, pause and reflect on the history, as well as the eclectic collection of art and sculptures. It's among the greatest business success stories worldwide, whose original roots trace back to copper, many years before the opening of the famous museum.

In 1848, Simon Guggenheim and his son, Meyer, fifteen years old at the time, arrived in the United States (Philadelphia) from Lengnau, Switzerland, joining the 19th century European exodus to America. Both father and son went right to work, peddling items including shoelaces and stove polish to miners in the Pennsylvania Dutch country. Soon, they started their own business and manufactured stove polish and later, 'coffee essence', a concentrate created from chicory.

By 1852, Meyer married Barbara, a nineteen year old girl he met on the ship over to the United States, and by 1873 had eight sons (Isaac, Murray, Solomon, Robert, Benjamin, Simon, William and Daniel) and three daughters, (Jenette, Rose and Cora). Unfortunately, Robert died at a young age, and Benjamin lost his life in the sinking of the Titanic, in 1912. He had boarded at Cherbourg, France and, as stated in books and movies, 'went down like a gentleman'.

Simon died in 1869, at seventy-six years old, and Meyer, with his exceptional business mind, expanded the business by becoming a wholesale spice merchant, manufacturer of lye, and importer of lace and embroideries.

The Origins of a Copper Legacy

In 1881, Meyer heard of a lead and silver mine, in Leadville, Colorado, that was flooded and for sale. His induction into the world of entrepreneurs was when he purchased interests in two Colorado mines - the A.Y. and the Minnie. One of his sons, Solomon, went to Mexico in 1891 to supervise the construction of a smelter in Monterey that dominated copper, lead, and zinc mining. He amassed a fortune, and by the end of World War I, at age thirty-seven, along with his remaining seven sons, controlled more than seventy-five percent of the world's supply of copper, silver and lead.

Meyer Guggenheim

Meyer GuggenheimPhotograph courtesy of Wikipedia

But, that was just the inception of a fascinating story that still continues: Meyer and his sons saw the future of their philanthropic endeavors and personal achievements and, as a family, were consistently committed to excellence.

The Guggenheim baton was passed on to another generation, starting with Daniel's son, Harry Frank Guggenheim, one of the fourth generation of Guggenheims, and now with Peter Lawson-Johnston, the author of Growing Up Guggenheim: A Personal History of a Family Enterprise , who brought the sixth generation into the Guggenheim museums located around the world.

"My first job was as a newspaper reporter for the Baltimore Sun," says Peter Lawson-Johnston, the great grandson of Meyer Guggenheim, grandson of Solomon Guggenheim and Honorary Chairman of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation that operates all the museums. "One day I walked into the office and the editor asked me if I knew anything about boats. I said no. He informed me that I was the 'yachting editor' in addition to writing a column "Rounding the Buoy". I covered races on the Chesapeake Bay. After that, I was sales manager of a remote feldspar mine. At some point I was sent to Malaysia for a crash course in tin mining, and eventually became chairman of Pacific Tin Consolidated Corporation. They acquired a small company in Spruce Pine, North Carolina, and I was there for two years learning the mining business and becoming sales manager. Pacific Tin was changed to Zemex, and subsequently we sold that company."

During that period, Lawson-Johnston was a director of the Kennecott Copper Corporation that owned many mines. Among them, the Bingham Canyon Mine, outside of Salt Lake City, and a huge mine in Chile, until the company was taken over by Standard Oil of Ohio, and is now controlled by Anaconda Company. On a personal note, my grandfather, whom I knew very well when I was a kid, shared some marvelous stories that are in my book. One family story is that my grandparents, who ate like canaries with my grandfather drinking soup that was boiling hot, had copper- lined stomachs. I also have some small copper pieces on my desk that I've inherited from the family, mostly ashtrays and things you can rest your pencils on.

"I gave my son, Peter Lawson-Johnston, Jr., most of the family copper memorabilia, including a huge bar that rolled off the assembly in Chile, when the Chuquicamata mine went into operation. It still has a label on it commemorating the occasion."

Meyer Guggenheim died in 1905, and his sons reorganized into Guggenheim Brothers, dominating the mining industry throughout the world. With the help of The Journey into the ArtsBetween 1929 and 1930, when Solomon was sixty-six, he collected modern paintings by well-known artists such as Kandinsky, Chagall, and Klee. His collection was installed in his private apartment at the Plaza Hotel, in New York. Coincidently, his niece, Peggy Guggenheim, opened Guggenheim Jeune, a commercial art gallery in London and represented avant-garde artists like Jean Cocteau, Kandinsky and Yves Tanguy. Eventually, under the auspices of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Solomon opened the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, in New York, to showcase his collection of American and European abstract artists, while Peggy opened Art of This Century, a gallery-museum on 57th Street, featuring her own collection that included Jackson Pollock and others. In 1943, Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the great architects of all times, designed a permanent structure to house the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, and over the next fifteen years would create approximately 700 sketches and six separate sets of working drawings for the building.

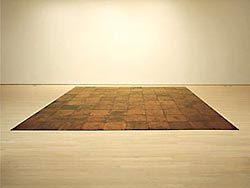

Andre, Square 377

Andre, Square 377 Carl Andre: Sculpture 1958-1974. Kunsthalle Bern, 1975

Catalogue raisonné by Angela Westwater and Andre; p. 27

"I met Frank Lloyd Wright when I was young at a meeting at the Plaza Hotel in my grandfather's apartment," recalls Lawson-Johnston. "That's where I was first exposed to his collection of art hanging on the walls."

In 1959 the Guggenheim Museum opened to the public, six months after Wright's death. The breathtaking architecture of the building and the art inspired controversy and debate, but private donations lead to the accumulation of works by Pissarro, Picasso and other renowned artists. In 1997, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain, opened and was hailed as another architectural masterpiece. Other museums, including the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, and the Guggenheim Hermitage Museum at the Venetian Resort in Las Vegas, followed. All of these museums are credited to the success of Meyer's original vision and success with the copper mines.

Copper Influence in Today's Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Brass plaque at the entrance to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Photograph courtesy of CDA

Brass plaque at the entrance to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Photograph courtesy of CDAWithin the walls of the Guggenheim, especially in New York, many highlights of copper and other alloy works are on display.

"There is a large circular brass medallion set in the Guggenheim lobby, just inside the front entrance," says Gregg LeFevre, of LeFevre Studios, in New York, who didn't create the above medallion, but has created pieces around the city like the Library Walk, Herald Square Gates, Union Square Timetable, and more. "As with all metal work set underfoot, if it is designed correctly, then foot traffic brightens the high areas and time darkens the inset areas. The work takes on the look of a deep relief, even though it may not be."

The piece has been stepped on as many as eight-million times by the forty-million visitors entering and exiting the museum since it's opening in 1959.

The 10 X 10 Alstadt Copper Square, by Carl Andre, occupies an essential transitional position in contemporary art. Historically, it rests within the more recent context of ideational gestures that began with the early paintings of Frank Stella. The copper square is defined by the work and the spectators, who are free to walk across it. Andre, known as one of the founders of the minimalist sculpture movement, who spent years as a freight-train brakeman, produced sculptures of elemental, classic form and his works, including his copper pieces, reflect the raw pieces found in quarries, shipyards and other places.

Another notable copper work in the Guggenheim collection is Donald Judd's, Untitled, which is ten units with nine-inch intervals that span from the floor to the top of his work. According to information provided by the Guggenheim Museum, Judd abandoned painting when he recognized that "actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface" and moved into three-dimensional art with knowledge that artists of his generation used the physical environment as an integral aspect of art. Minimalist sculpture had already broken the thread of illusionist conventions by translating compositional concerns into three dimensions. This gave artists a new venue in which to use copper and its alloys. Untitled possessed simple shapes with a slightly recessed upper surface, readily intelligible as a whole and avoids the compositional effects that dilute a work's power.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- The Guggenheim Legacy: From Copper to Contemporary Art

- Amy Kupferberg, Alchemy and Meaning

- Steven Whyte Finds Common Ground with His Real-Life Bronze Portraits

- The Statue of Liberty: A Shining Example of Copper's Endurance

- Brass Menagerie Showcases American Brass of the Aesthetic Movement