The Changing Nature of Verdigris

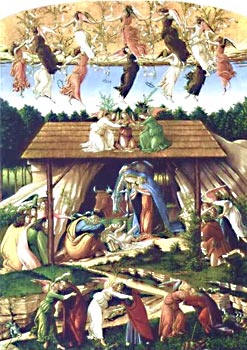

Sandro Botticelli, The Mystical Nativity, circa 1500

Sandro Botticelli, The Mystical Nativity, circa 1500Photograph courtesy of Karen Mortensen

Stroll through any museum containing paintings by the Masters of the Renaissance, and you will see evidence of verdigris. What is this substance with a foreign-sounding name? Verdigris is a green compound that forms on copper as it weathers. It was used as a pigment from the Middle Ages until the 19th century. The word "verdigris" literally means "green of Greece" (vert-de-Grice), and has similar variations in Middle English and Old French.

Painters valued verdigris for its rare, luminescent green color, but using it posed challenges.

"A green copper pigment like verdigris is notorious for behaving in ways that are inconsistent and not fully understood," explains Arthur DiFuria of Moore College of Art & Design. DiFuria is Assistant Professor and Visiting Scholar in Art History and Curatorial Studies, and specializes in Northern Renaissance art. "What we look at now isn't necessarily always what it [a painting] looked like when it was done, or what the artist intended."

The fact that verdigris is an exceptionally changeable pigment is its most fascinating aspect. All pigments change somewhat over time, but verdigris can have wide mood swings. While it is generally thought to be lightfast in oil paintings, it has very little light or air resistance in other media. In an effort to protect the color, painters would sometimes apply verdigris along with layers of varnish.

Not only was verdigris an unstable pigment, but different workshops most likely mixed it in different ways, according to DiFuria. These differences could affect the way the pigment changed over time. For example, DiFuria explained that much of the verdigris Botticelli used turned brown with time, with the browning being due to the mixing process. While the paintings looked as Botticelli intended at the time, they went through a chemical process over the years that he could not anticipate.

Despite its drawbacks, verdigris was intensely popular among painters for hundreds of years, from Europe to Egypt to China-and most likely, a number of other places. It fell out of favor only because green pigments that were more stable became available and because verdigris was poisonous. The only thing that prevented people from using it during the Renaissance was the price-verdigris was expensive. DiFuria explained that the use of verdigris is associated with the Renaissance because the arts in general took off at that time. People with power hired painters from the best workshops and provided them with the finest materials. Of course Botticelli used verdigris; the expensive material was made fully available to him. Artists of lesser means might have had to choose something less expensive.

DiFuria added that Florence, Vienna, and Venice were cities well known for Renaissance art. The Bellini workshop in particular, including Jacopo, Gentile, and Giovanni, "did astonishing things with the color green," according to DiFuria, who added, "I'd be shocked if it wasn't verdigris."

This raises another intriguing aspect of the historic use of pigments. Many times it's impossible to know what pigment was used in a painting without laboratory analysis. Yet many thousands of paintings remain unanalyzed. Take The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck, for example. The glowing green in this masterpiece is most likely verdigris, but DiFuria himself is not sure. On the other hand, Botticelli's Mystic Nativity does use verdigris as its source of green, although the color has browned slightly over the years.

More research needs to be done to identify paintings that use the pigment. And hopefully over time, researchers will develop a better understanding of exactly how and why the shades of green differed in various workshops' pieces. For now, verdigris carries with it a certain mysterious uncertainty, refusing to be pegged down. Perhaps that's not a bad thing with art.

Also in this Issue:

- Copper Keepsakes to Make your Holiday Shimmer

- Reggie Farmer: Modern Day Coppersmith

- The Changing Nature of Verdigris

- Weathervanes of Maine Continues the Colonial Craft of Copper Weathervanes

- Metropolitan Museum Offers Rare Viewing of Lorenzo Ghiberti's Gates of Paradise, Magnificent Renaissance Masterpiece