Shedding Light on the Legacy of Tiffany

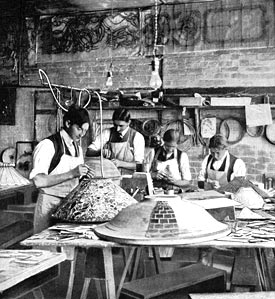

Early Tiffany craftsmen assembling shades.

Early Tiffany craftsmen assembling shades.Courtesy of The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass

One of the most stylish contributions to the lighting world are Tiffany leaded glass lamps, created by Louis Comfort Tiffany, an American whose artistic talent and career are still celebrated today. The pieces are referred to as 'art nouveau' and copper foil played an important part in the construction of these coveted works of art. These pieces are actually referred to as 'leaded glass' windows or leaded glass lamps because Tiffany sought to eliminate all painted (or stained) details from his window, although the public addresses them as 'stained glass lamps'. His work was celebrated and critically acclaimed due to the brilliant, rich colors that were actually fused in the glass while it was in a molten state rather than painted onto the surface, as was typical. In today's market, an original Tiffany lamp can fetch as much as $8 million at auction.

Although Tiffany began his career as a painter, he worked at several glasshouses in Brooklyn. The first Tiffany Glass Company began in 1885, and later became known as the Tiffany Studios. His magnificent leaded glass lamps are well known throughout the world and are highly collectable. The actual Tiffany Studios remained in business until 1932, but anything 'Tiffany' is still a collector's dream. And, according to Lindsy Parrott, Director/Curator of The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass, in Long Island City, New York, which is well known for its world class collection of Tiffany lamps, a copper foil technique was used by Tiffany's staff to assemble small pieces of glass into elaborate lampshades and portions of windows.

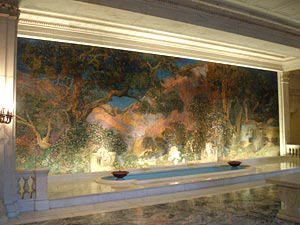

The Dream Garden, a mosaic by Louis Comfort Tiffany based on a Parrish painting. On view at the Curtis Building in Philadelphia.

The Dream Garden, a mosaic by Louis Comfort Tiffany based on a Parrish painting. On view at the Curtis Building in Philadelphia.Photograph by Bruce Andersen.

"Lead cames were traditionally used to fabricate stained glass windows, but many of Tiffany's windows are a combination of this lead came and copper foil technique," says Parrott. "Leaded-glass lampshades are an idea grown out of fabricating windows. A woman named Clara Driscoll is responsible for the development of leaded shades. She worked for Tiffany and supervised a department of women engaged in selecting and cutting glass for windows and mosaics. She combined ingenuity, artistic talent and familiarity with the technical process of selecting colored glass to create a new form made of leaded glass---the lampshade. Prior to her introduction of the leaded-glass shade, in approximately 1898, Tiffany was already producing lamps, but they were made of blown glass and decorations were limited to modulations and swirls of color and pattern. Leaded glass lampshades, however, could be produced in all manner of designs - from straightforward geometric patterns to complicated floral designs. Although the lampshades were created on a large scale, each is unique and one of a kind because of its glass selection.

According to Parrott, although Tiffany used the copper foil technique to wonderful effect, he was not the originator of this technique. A man named Sanford Bray was awarded a patent in 1886 for the method of joining glass mosaics with copper foil. However, the Neustadt Collection's important archive of flat and pressed glass used at the Tiffany Studios to create the famed windows, lamps and mosaics, includes nearly 300,000 individual pieces of glass, and is the only one like it in the world. It provides a fascinating portal into glass chemistry at the turn of the century. Glass recipes were carefully guarded secrets because certain colors, color combinations, opacities and patterns were difficult to achieve.

"Tiffany's vast family fortune provided him with the means to fund costly and time consuming glass experiments, which gave him a leg up on his competitors," she says. "It's important today because reproductions of Tiffany lamps abound and many of them replicate original Tiffany designs. In these instances, it is the glass, and oftentimes only the glass, that separates the authentic lamp from the forgery."

Tom Venturella, Sr. Conservator of Venturella Studios in New York City, restores Tiffany glass and explains the copper foil process used in these lamps.

Peacock Library Lamp, 1900-1910. Leaded glass, bronze with blown glass and glass inlay.

Peacock Library Lamp, 1900-1910. Leaded glass, bronze with blown glass and glass inlay. Courtesy of Tiffany Studios.

"When you're speaking of lamps, where glass is cut for shades, it's laid out on a light table so we can see what the colors look like when we're creating it," he explains. "Once the glass is cut and the selection approved, or used for repairs, we use copper foil. Today's copper foil comes on rolls that appear like tape with an adhesive on one side. It's much narrower than Scotch tape. Tiffany used large sheets of copper, laid it flat and coated one side with beeswax and then cut it into various strips and sizes. Because he didn't have adhesive, he used the beeswax to keep the glass in place. When that piece of glass was wrapped in copper foil it was placed on a wooden mold that shaped the finished product, which could have an 18 or 20-inch dome. The mold mimicked the final shape. This process is repeated with every piece of glass within the lamp making it a timely process."

According to Venturella, every piece of glass gets wrapped no matter how large or small. When these copper foil pieces of glass are laid on the mold it becomes a three-dimensional object. The next step, to hold it together, is to flux the inside of that lamp, by using 60% lead and 40% tin solder.

"Fluxing is soldering all of the copper together so it holds, and it's usually a liquid flux like oleic acid or zinc chloride," he continues. "The entire lamp is soldered together piece to piece on the mold and then the lamp is carefully lifted. We also flux the inside of that lamp because the copper is exposed on the inside at that point. The outside has already been done. The process is repeated so all of the exposed copper edges are soldered, creating stability in these lamps. There's an aperture ring at the top of the lamp, which is usually brass, and all of the copper is soldered to it. The bottom of the lamp, the widest part, is also called an aperture and has a brass ring. For example, if you're making an 18-inch diameter lamp you turn that lamp over after removing it from the mold, and it's sitting on its smaller aperture---literally upside down---so you're gazing at the inside. Therefore, you'd also have to have an 18-inch brass ring soldered to the open copper edge on the large bottom opening. If there's no brass ring soldered to the open copper edge on the large bottom opening, and if, for any reasons the copper foil gets torn off the pieces of glass it starts to unravel."

Fabrication of a leaded-glass lampshade, application of solder over copper foil-wrapped edge of glass.

Fabrication of a leaded-glass lampshade, application of solder over copper foil-wrapped edge of glass.Courtesy of The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass

When that procedure is finished, according to Venturella, the Tiffany lamp will be cleaned of all the flux, which provides a silver luster that covers the copper foil. He explains that when Tiffany wanted to change the silver color he electroplated them with copper, so the viewer is gazing at a shiny copper look rather than silver. All of the leadlines are copper.

"From there, Tiffany would start to patinate---copper is wonderful base for patinas," he says. "They could be done in chocolate browns or antique solutions, usually with copper sulphate or cupric nitrate. And, that's just the shade! The bases of these lamps were made as if they were table lamps, but they were also hanging lamps, referred to as a chandelier. The bases of the table lamps were bronze and the bronze had the same treatment as the shades, so they'd be electroplated in copper as well. Usually, the patina matched the lamp. While there are certain styles of bases that went with specific shades, many times bases were interchanged with shades. Certain molds or styles weren't interchangeable like the Wisteria that boasts a trunk base, or the Grape Arbor, also with a tree trunk base. An Apple Blossom lamp just went for auction at Sotheby's---for $640,000."

Venturella also explains that Tiffany used copper in many of his other objects---desk sets, candlesticks and other odds and ends---because it's a good base for patinas.

"Many people want to own Tiffany, and I always see waves of collectors coming into the market," says Arlie Sulka, Tiffany Expert and Antiques Roadshow appraiser, who has visited museums, client's homes and collectors worldwide. "I was hired by Mrs. Lillian Nassau, considered the leader in the field for many years, and took over the store in 2006. Lillian Nassau is considered to be the first person to recreate the interest in Tiffany and was buying these lamps when no one else (was buying). She's been credited with single handedly establishing this market. She invited museums to visit her store and see them, then auctions picked them up, but she was at the forefront. Rock stars and people in the entertainment world bought some, which stimulated the market, and now, if there's ever a museum show on Tiffany, they come to us to lend."

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Shedding Light on the Legacy of Tiffany

- Copper Lantern

- Artist of the Elements: Lavelle Foos

- Brookgreen Gardens: America's First Sculpture Garden

- Tiffany by Design on View at Frist