George and Gerard Tsutakawa: A Family Legacy Shaping the Seattle Identity

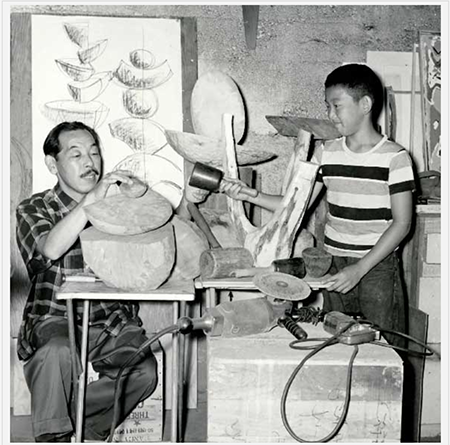

George in the Studio with his son, Gerard.

George in the Studio with his son, Gerard. Photo by Lon McKee, courtesy of Wing Luke Museum.

Seattle has been forever changed by the public art of George (1910-1997) Tsutakawa and his son, Gerard.

Their bronze sculptures are touchpoints for their community, shaping its identity.

A new exhibit at Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience, Gerard Tsutakawa: Stories Shaped in Bronze, takes a look at the renowned sculptor’s 50-year career, his process and his father’s influence on his work.

On view through April 17, 2022, The Seattle Times describes the exhibit as presenting visual diaries of the process of making public bronze sculptures from fabrication to installation, noting how playful visitors engage with the finished pieces as tactile elements of the open city.

Wing Luke has also organized a walking tour and virtual tour of both George and Gerard’s works around the city center, highlighting 14 pieces places throughout Seattle.

“Through the exhibit we hope to give viewers the background information to Gerard's process from the initial design to the fabrication and installation of his public sculptures that we regularly see and visit in the Seattle area and beyond,” says Blake Nakatsu, exhibit developer and YouthCAN Program at Wing Luke.

Urban Peace Circle, Gerard Tsutakawa, 1994. Located at Sam

Urban Peace Circle, Gerard Tsutakawa, 1994. Located at Sam Smith Park on Martin Luther King Jr Way South.

Photo courtesy of Wing Luke Museum.

The exhibit recalls the history associated with George Tsutakawa's public artwork legacy and influence it has on Seattle, while emphasizing Gerard Tsutakawa's current contributions to Seattle's urban fabric, communities and culture, said Seattle-based architect Rachael Kitagawa, a close family friend who curated the exhibit.

“It reflects the benefits of thoughtful art and design and how it unites with positive interaction regardless of age, race, gender, social or financial status,” Kitagawa says.

Inspired by the abstraction of nature in his sculptures, Gerard Tsutakawa often studies from Pacific Islander or Aboriginal cultures, delving into Polynesian, Maori and Southeast Asian craft and folk art.

In a video, Tsutakawa describes the inspiration of his mother’s Japanese fan collection for the canopy and door pulls for the Wing Luke museum (2008).

Another sculpture well-known to Seattle residents is The Dragon (1978) at Donnie Chin International Children's Park. The six-foot bronze is made for children to climb on. Bronze is conductive of heat so he ended up backfilling it with sand. Bronze also transfers heat quickly so that the sand absorbs the heat.

“Gerard has embellished public spaces with timeless sculptures that are meant to connect people to the locations where they reside,” said Nakatsu.

Kitagawa said the Tsutakawas works are important because of how they change public spaces and invite interaction.

George Tsutakawa left an indelible imprint on the urban fabric of Seattle, transforming the perception of public spaces with his fountains and sculptures. His son, Gerard, continues to do so with his work. “Gerard Tsutakawa is an established and celebrated artist in his own right with his own distinct style,” Kitagawa says. “He assisted in creating and managing many of George's historic pieces and continues to maintain them.”

For Gerard art can be approachable and accessible by pulling inspiration from translatable natural forms and visual culture and encouraging the public to be a part of the artwork through interaction.

His work is whimsical, fun, and relatable to people of diverse backgrounds, which engenders love of his pieces.

“His personal relationships with community organizations and the art he has created for them have helped to shape not only the spaces but the identities of these groups,” Kitagawa says. “Many of us have grown up surrounded and touched by both of their work.”

Physically and culturally his work has a presence for experience and wayfinding. Kitagawa said he is also important socially in the community.

“Gerard often works closely with the communities he creates art for,” she said. “ They feel like he has truly thought about their identities and missions; and all the community groups I've spoken to have wonderful things to say about his work and as a person.”

Gerard’s approachable and accessible art is imbued through his process.

“Gerard's method of backfilling his bronze sculptures with sand, making them touchable and interactive in the hot summer sun, defies the traditional mantra of ‘do not touch the art’ and allows viewers to become participants,” Nakatsu says. “When confronted with Gerard's work, their large-scale stoic forms leave such an impression on you that they become recognizable waypoints and shared experiences woven into our own stories and daily lives.”

Kitagawa noted Gerard's thoughtful and intentional attention to detail and purpose.

“His art is designed to promote interaction with the pieces and the communities experiencing the,” Kitagawa says. “The memory of them becomes personal, whether you let your kids play on it, took a selfie with them, watched the water cascading down it; it becomes an active/physical part of your experience versus the passive type of art.”

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- History Cast in Copper

- Toledo Museum of Art Adds Two Monumental Sculptures

- Deb Zeller: Capturing the Legacy of Family and Agribusiness Through Bronze

- Mr. Rogers Sculpture Unveiled at Rollins College

- George and Gerard Tsutakawa: A Family Legacy Shaping the Seattle Identity