Typothecary: Continuing the Art of Copper Letterpressing

Megan Zettlemoyer in front of her antique printing press at Typothecary in

Lancaster, PA.

Photograph courtesy of Megan Zettlemoyer.

Megan Zettlemoyer’s paint strokes sweep in arc that is both abstract and organic. The artwork invites contemplation as the once vibrant blue copper oxide edges toward green as the pokeberry ink fades from lively mauve to a dusty rose.

It is no accident the art is fading.

Zettlemoyer is the proprietor of Typothecary, a letterpress in the thriving artist scene of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. As a sideline, she has created a series of foraged ink pieces in which colors from bittersweet, pokeberry, avocado pits and black walnut bark dance around the sweeps or drops of ink made of copper oxide. The original colors are preserved in prints but the original paintings, which are on display in her letterpress studio, fade.

A graduate of the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, Zettlemoyer, now 35, started her career as a graphic designer but fell in love with the hands on work of letterpress printing.

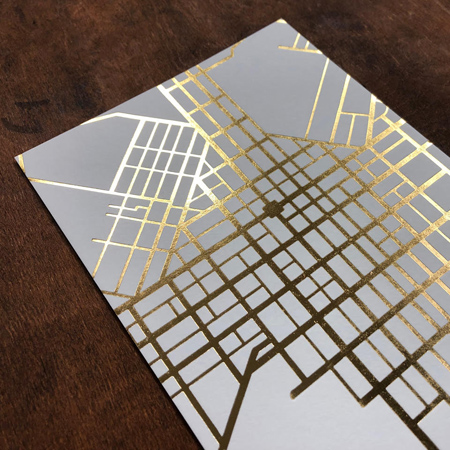

Detailed closeup of the copper foil printing press methods at Typothecary.

Detailed closeup of the copper foil printing press methods at Typothecary. Photograph courtesy of Megan Zettlemoyer.

She discovered the thrill of DIY ink after happening on the book Make Ink: A Foragers Guide to Natural Inkmaking by Jason Logan.

Making copper oxide is a simple process of mixing copper with cleaning strength vinegar and salt. She was intrigued by the science of the process.

“I feel like it just kind of fell out of me,” Zettlemoyer says of the design. “I like the organic nature of the ink. I like the rough edges.”

Her art is an outgrowth of her eight-year-old letterpress studio. Among her oldest presses are two from the late 1800s, a Chandler & Price Platen Plus made in Ohio and a Heidelberg Windmill.

She said at first the presses were intimidating.

“I never wanted to print on this press,” she said of the motorized Heideberg.”It’s terrifying to watch. Then you start doing it and it’s so much fun - knowing you can be in control of this complicated piece of machinery.”

Her copper foil work has become a favorite for wedding invitations. It adds glitz, she said, without being too shiny and garish.

Copper plates aren’t used as much in letterpress these days, she says. Clients often chose polymer due to the cost but Zettlemoyer noted polymer plates crack and in a large run can overhead and warp.

For big jobs or clients that will need more items printed, she goes to copper plates.

One such client was a Pennsylvania cigar maker, which wanted to highlight its locally handmade product by having all aspects of the cigars handmade, including the labels. She designed and printed more than 100,000 cigar bands.

She had a copper plate showing a street map of the city of Lancaster, something that will certainly be used repeatedly as the city gains

Three years ago, Zettlemoyer, who also teaches at the Pennsylvania College of Art and Design, joined with other printers in Lancaster to found an annual print crawl. Each year attendance has increased.

This September an estimated 1,000 patrons visited the crawl.

Zettlemoyer said her graphic design background has served her printing business well. And the letterpress is serving her art, too: Zettlemoyer has designed and printed boxes for notecards of the foraged ink paintings. She hopes to have them available at future art walks and makers markets in Lancaster.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- The Pilgrim: A Bronze Beacon for Philadelphia

- Browne Designs: Forged in Flame and Copper

- Typothecary: Continuing the Art of Copper Letterpressing

- The Bronze Works of Brookgreen Gardens

- Rare Calder Brass Earrings Sold at Lark Mason Auction