Collaborating with Copper through Nature

Cathy Vaughn was working as a graphic designer and had no prior experience in working with metals when she got her hands on copper about twenty years ago.

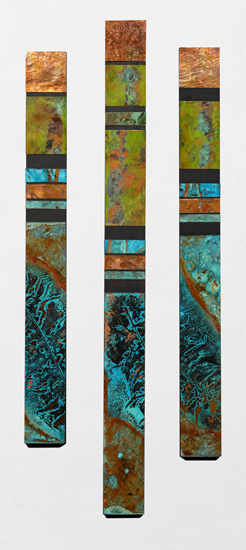

Totem Tryptic #585 by Cathy Vaughn.

Totem Tryptic #585 by Cathy Vaughn. Photograph courtesy of Cathy Vaugn.

“When I started out working in graphic design it was a very hands-on medium,” Vaughn says. “It was before computers were a part of the process.”

As computers began taking center stage in her profession, she turned to copper when she found that her soul was no longer being fed by her profession.

“There was a lot of drawing and a lot more tactile interaction with materials, which is something that is very important to me,” she says, referring to the aspects of graphic design she appreciated in the past.

Vaughn’s path to becoming a fine artist and coppersmith began with satisfying a curiosity along with being up for a new challenge.

“I did some research and taught myself how to work with it,” she says. “I was looking for a medium I had never worked with before.”

She appreciated the accessibility of copper and first began working with it without the use of any heat.

“I could find copper in the hardware store,” Vaughn says. “That is how I initially started out — with copper tubing, copper pipe and fittings.”

The first pieces she created centered on functional needs at her home.

“I would make a trellis and other things for my garden and started making gifts for people,” she says. “I was an artist already, so I just wanted to make things that were nicer than something you would buy off the shelf.”

The more she began working in copper, the more she realized it was a metal that worked with her instead of against her.

“It’s easy to bend, easy to patina — it seems like something that wants to work with you,” she says.

Over the course of two decades, Vaughn’s handmade work has evolved into two different categories: structural work showcased on her website and her fine art pieces found at Copper Abstractions.

Among her fine art pieces are a series devoted to an infusion of copper with nature. Vaughn was led to a technique involving tree leaves when she realized she wanted to bring more color into a copper privacy screen she was working on about four years ago.

“I bought a sheet of copper and put acid on the sheets and did a loose composition with a dozen different types of leaves and was experimenting,” she says.

Vaughn left the piece alone for a week and was pleased with the results that enabled her to develop images and textures on copper.

“The acid reacted with the leaves and the copper,” she says. “The acid dried slowly and the copper had these brilliant colors — I saw a striking and very clear image of the leaf by doing this.”

After her first experiment, she set out to try to replicate the process and experiment further over a six-month period.

“To make it happen again and to determine what are the values that change the color,” she says. “To see if it would change if you spent longer with it and can you do it in a more compressed amount of time.”

Closeup of Cathy Vaugn's process.

Closeup of Cathy Vaugn's process. Photograph courtesy of Cathy Vaugn.

During her time devoted to experimentation, she also did research on leaves.

“Different types of leaves have different levels of tannic acid in them,” she says. “They also have water in them, sugar and salt — all that has an impact on the outcome of the process.”

She also began playing with different types of acid in addition to muriatic acid.

“Vinegar is acid and you can use different strengths of that,” she says. “Ammonia will turn copper blue — there are certain things I can do to influence the color.”

However, her intent isn’t to contrive the outcome.

“I’m not trying to make a color,” she says. “I’m open to whatever color happens. It’s a wild card of whatever chemistry is in the leaf.”

Most of the copper abstractions she makes are face-mounted to a wooden box frame and are intended to hang on a wall. Sizes of her pieces range from 3’ x 4’ down to 3” x 3”.

“A lot of people look at my work and ask if that’s a painting,” she says. “Usually there is conversation about what they are looking at — they don’t understand they are looking at something on metal.”

The location of Vaughn’s studio in Richmond, Virginia serves as a great resource for materials for her work.

“I moved my studio to a wooded area so that I had more access to leaves,” she says. “I was working in the city and I was driving a lot of time to get my leaves.”

She likes being able to identify leaves she comes across to work with, so pays visits to such places as the Lewis Gintner Botanical Garden in Richmond.

“I do research there and it helps me identify things i might find,” she says, adding, “I have done some work with the James River Association to meet with their botanists to do some leaf collecting.”

Vaughn has focused mainly on leaves you would find in the state of Virginia, but looks to broaden her reach in the near future.

“I’m applying to the National Parks Association to do a residency at some of the national parks so it would get me out of the East Coast area of leaves,” she says.

Ginkgo leaves and Royal Empress Paulownia leaves are some of her favorites.

“Sassafras also do really well, deciduous magnolias, all kinds of maples and poplars and chestnut oak,” she says.

Vaughn works with green, not dried leaves.

“That is something I discovered early on in my process,” she says. “The dried leaves don’t have any water in them and any chemical in them would be in crystallized form.”

Since green leaves are only available during certain months of the year, she makes an effort to preserve some.

“I do brine some of my leaves in non-iodized salt,” she says. “I keep them in Mason jars and that will keep the leaves anywhere from six months to a year.

The entire process from start to finish for Vaughn to achieve the impression she is seeking, requires waiting anywhere from three days for small leaves, up to two weeks for larger leaves.

“Some things that influence it are the ambient temperature,” she says, adding that if it is warm outside it speeds up the process. In addition to heat, time, rain, and the chemicals present in each of the elements gives her a range of color and texture.

Her favorite part of the process in making her copper abstractions has to do with the outcome, but there is still a rinsing process that acts as the final step to keep the copper from continuing to oxidize.

“When you unwrap it and you pull the leaves off, that is the most fun part because you get to see the color,” she says.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Rockefeller Center Basks in Bronze During the Holiday Season

- Collaborating with Copper through Nature

- New Exhibit at The Jewish Museum Showcases More than 80 Rare Hannukah Lamps

- Trumpets, Weird and Wonderful Showcases the Art of Brass Instruments

- Armenian Museum of America Opens New Gallery