The Bronze Mission of Sculptureworks

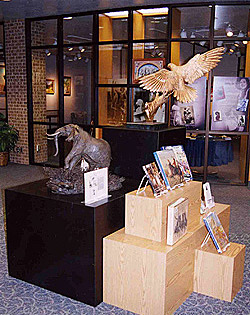

Mountain Fishing by Sculptor Rosetta on display at the Hurst, TX, Public Library.

Mountain Fishing by Sculptor Rosetta on display at the Hurst, TX, Public Library.Imagine driving bronze sculptures around the country in a truck, setting up exhibits every three months and rotating them throughout various states. Some might think you’d be crazy to spend your time like this. But for David Wiegand, it’s another day doing what he loves.

Wiegand isn’t an artist. He’s never worked with bronze or copper and he can’t even draw well. But Wiegand is on a mission, one that supplies bronze sculptures to public libraries. Initially he assembled an exhibit at the Bedford Texas Public Library which featured a bronze sculpture called The Need to Know by Hollis Williford, of a young boy reading a book with his head resting against his loyal dog. The exhibit was such a huge success that Wiegand innately understood how deeply it affected everyone who came in contact with it. “The library is the cultural center of many cities,” he says and this is where an arts-deprived public looks for inspiration. So, in 1998 he started Sculptureworks.

Artists consign pieces to Wiegand who tours them through libraries. Each exhibit lasts 90 days and is utterly free.

“The costs come out of my pocket,” Wiegand admits. He’s not in this to make money; sales defray his costs after a commission is paid to the sculptor. From Tipton, Indiana, to Bensonville Illinois, and Hurst Texas, Wiegand has installed bronze sculptures at over 200 libraries and exhibits can be as large as 135 pieces.

Sculptor Paul Oestreicher's works

Sculptor Paul Oestreicher's worksYou’re likely to see graceful animals, people, and abstract shapes. One bronze piece, a happy golden retriever nicknamed Bob created by Paul Oestreicher, sums up the experience of many children with the bronze sculptures at their local libraries. A little girl in Cascade, Michigan wraps her arms around this inanimate bronze dog saying to it, “You be a good dog, I’ll see you tomorrow,” she pets the dog and kisses it - a scene that has played out at many libraries. “I think copper gives artists the ability to transform images,” Wiegand says. The kids are able to touch a mountain lion, a dog or an eagle, and talk to it. At most galleries no one is allowed to touch works on display. “The acids on your hands will degrade the metal,” Wiegand says. “But with bronze you just need to rub and clean it twice a year.”

When he hears parents tell their kids to not touch the sculpture, he says it’s okay, giving children a tactile experience with bronze sculptures for the very first time. “By definition good sculpture makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand up,” he says and this kind of emotional and visceral reaction is what Wiegland hopes to see. Sculptureworks also has the artists pieces on display via his website which are also for sale.

“This opened a door I didn’t even know was there,” Wiegand says of his passion is helping libraries. In truth Sculptureworks has opened many doors, for artists and the public, by bringing a new generation their first understanding of the power of bronze.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Classic Bells: Continuing the Holiday Tradition with Brass

- Harold Monk: Sculptor of Sophisticated Metal Art

- The Anatomy of Copper

- The Bronze Mission of Sculptureworks

- Rare Bronze Medieval Aquamanile Highlighted in New Exhibition at The Jewish Museum