Collecting Colonial Era Copper Prints

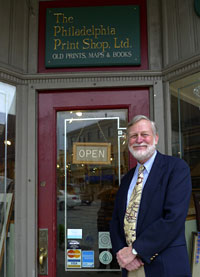

Co-owner Donald Cresswell standing in front of the Philadelphia Print Shop

Co-owner Donald Cresswell standing in front of the Philadelphia Print Shop Photo by Rebecca Troutman

The Philadelphia Print Shop sits on a sunny corner in Chestnut Hill, established in 1982 in an old building surrounded by cobblestone streets. This historical neighborhood of Philadelphia invokes a colonial era in which copper flourished as a staple in printmaking. By the time Paul Revere engraved one of the greatest pieces of American propaganda depicting the Boston Massacre in 1770, printmaking had established a 300 year history in Europe as a vehicle for fine art, cartography, political cartoons, depicting scenes of social importance, and news. For many centuries copper was at the center of it all, and the Philadelphia Print Shop supplies curious browsers and serious collectors access to one of the largest collections of antique maps, prints and resource books in the United States.

Readers may recognize the co-owners of the Philadelphia Print Shop, Donald H. Cresswell and Christopher W. Lane, because they are widely published historians and regular guest appraisers on the popular PBS program, Antiques Roadshow. The exposure has garnered Cresswell and Lane the rock star status among history buffs, and their expertise is often sought out by fans.

Antique prints were produced using a basic medium-be it stone, wood, or metal-and are usually grouped into three categories: relief, intaglio, and planographic. The most common type of print during the American Revolution was intaglio, in which the image is recessed into the copper. To create a print, ink is placed into the recessed areas, wiped away from the surface, and transferred to paper under high pressure. Intaglio prints can be identified by a characteristic platemark pressed into the paper that appears as a faint border.

The popularity of copper lasted several hundreds of years, from the 1420s to late 18th century. Printmakers preferred to produce intaglio prints using copper, and various styles evolved including engravings, etchings, aquatints and mezzotints. Copper was deemed best for the job based on its durability, availability, and properties that allowed for expertly detailed designs by freehand. However, with the advent of technologies in the early 1900s, copper was traded in for steel-a much harder metal which produced greater than double the impressions that copper could before the strain of the press eroded the vitality of the print. The invention of lithography in 1798 and later photomechanical methods has relegated copper plate printing to a small niche market of contemporary artists.

John James Barralet, "View of the Water Works At Centre Square Philadelphia," 2nd State

John James Barralet, "View of the Water Works At Centre Square Philadelphia," 2nd StateCourtesy of the Philadelphia Print Shop

"Copper is the traditional way to create a print," notes Cresswell, who admires the labor that goes into handmade copper prints. Although a typical engraving by hand would have easily taken three weeks for a craftsman working from sunrise to sunset to complete, "[copper] was probably easier to work with [than steel] as well as more artistic."

Copper did allow the artist to be more expressive and create warm scenes, but copper plates would wear down from constant pressings. Routinely, craftsmen were directed to engrave the same copper plate anew. Each time this occurred, its prints would be referred to as a second "state," third "state," and so on.

Occasionally small details or embellishments were added, such as in the second state of "View of the Water Works At Centre Square Philadelphia." According to Cresswell, this view of the Centre Square Waterworks, located today on the current site of Philadelphia's City Hall, was drawn by John James Barralet (ca. 1747-1815), an Irish artist who came to Philadelphia about 1795. The stipple etching, an intaglio process by which different sized small dots are arranged closer together or further apart to depict shadow and light, was done by Cornelius Tiebout. When the pressure of the press wore the copper plate down, the job of producing the second state was passed to engraver H. Quig. You will notice a very small man in the foreground between the two wagons that he added, Cresswell speculates, possibly to enliven the scene. However, the fourth state reveals that H. Quig was not pleased with the figure and had attempted to burnish him away, leaving a "light ghost" where he once was, produced 5 to 15 years later and colored by hand. The second state is extremely rare, ironically because Quig did not print many copies as a result of his presumed dissatisfaction with his out-of-scale figure.

Of the 20,000 maps and old paper prints in the Philadelphia Print Shop gallery, antique-hunters won't find one reproduction in the bunch. Cresswell and Lane believe that the vibrancy of the print aesthetics paired with "rigorously researched historic context" allow them to speak for themselves, and are very passionate about that philosophy. "Once upon a time," Cresswell says, reflecting on his academic passion and life's work, "I wanted to say something to staff about how I felt about what we did here. Every year I can look back, and I told them my greatest accomplishment is that we made a lot of people happy."

The Philadelphia Print Shop will celebrate its antique map collection throughout the month of September, 2009, featuring hand-carved prints produced using copper from the period between 1600 and the early 1800s. For those who would like more information on the basics of printmaking, Cresswell recommends the book How to Identify Prints by Bamber Gascoigne.

Resources:

Philadelphia Print Shop, 8441 Germantown Ave., Philadelphia, PA, (215) 242-4750

Also in this Issue:

- Grounds for Sculpture: A Marriage of Nature and Art

- Collecting Colonial Era Copper Prints

- America's First Copper Paint

- Depicting Nature in Metal

- Julia Child's Copper Pots Reunited at the Smithsonian